CTRL + ALT + DEPLETE

Resetting a dysfunctional immune system via the selective depletion of rogue cells is an emerging therapeutic strategy, having matured in the oncology space and now poised to take over in autoimmune.

Intro

Cell depletion therapies have completely revolutionized the way we treat B cell malignancies, offering the potential for complete remission or even cures. Excitingly, the clinical success of B cell depletion therapies (BCDTs) for oncology has inspired a number of new BCDT programs for autoimmune diseases. Given this unique inflection point for BCDTs, we’ve decided to compile an overview of the field and its history, highlighting some promising therapeutic modalities and opining on some ideas of where we feel the field might be headed next.

B Cell Depletion Therapy for Cancer Treatment

B cells are an immune cell type most commonly associated with the secretion of antibodies that physically mark cells, pathogens, and proteins for elimination. While B cells play an important role in fighting infections and preventing disease, they are also a common origin for cancers such as Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL), which accounts for ~4% of all cancer diagnoses in the United States. About 85% of all NHLs arise from B cells, referred to as B-NHLs.

The major goal in the treatment of B cell lymphomas is the selective killing of cancerous B cells and the establishment of long-term remission. Prior to the late 1990s, the standard treatment options for B cell lymphomas included radiation therapy and chemotherapy, which are effective at killing cancerous B cells, but are not very selective. Thus, these approaches were significantly limited by their off-target effects, damaging both cancer cells and healthy cells across different tissue types.

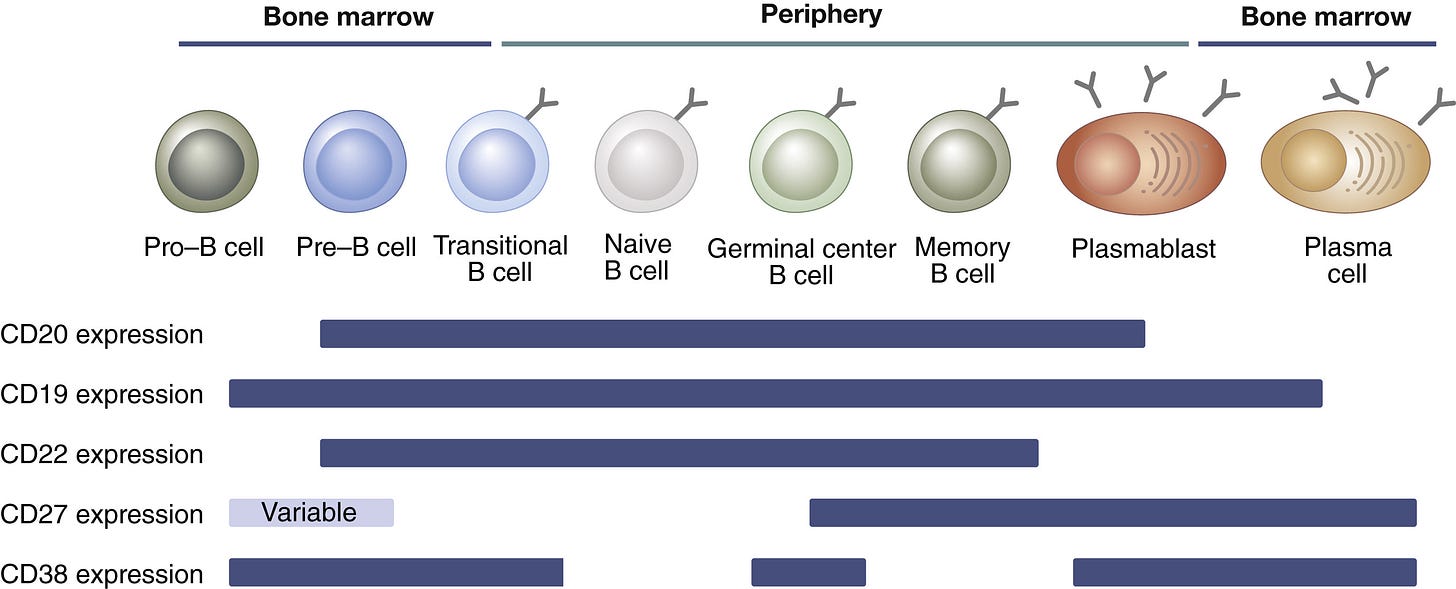

The demand for more precise treatments has driven the development of B cell depletion therapies (BCDTs)—a rapidly expanding class of treatments designed to selectively eliminate pathogenic B cells. BCDTs encompass a range of therapeutic modalities, with the most common being monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) designed to target unique cell surface markers expressed only by B cell populations (e.g., CD19, CD20, BCMA). Just as healthy B cells produce antibodies to eliminate pathogens, we’ve learned how to design and manufacture antibodies as medicines that specifically target B cells for depletion.

The most well-known and widely prescribed BCDT is a drug called rituximab (Rituxan, Genentech/Biogen), a mAb that recognizes the B cell surface protein CD20. While originally approved by the FDA as a monotherapy for the treatment of chemo-resistant B-NHL in 1997, rituximab combined with chemotherapy (i.e., R-CHOP) has quickly become the standard of care across several B cell lymphomas with an impressive complete response rate of ~76%.

Antibody-based therapeutics, such as rituximab, have played a pivotal role in the clinical advancement of BCDTs due to their ability to bind to cell surface receptors with high specificity and trigger immune-mediated target cell depletion. There are a few main mechanisms by which these cytotoxic processes occur:

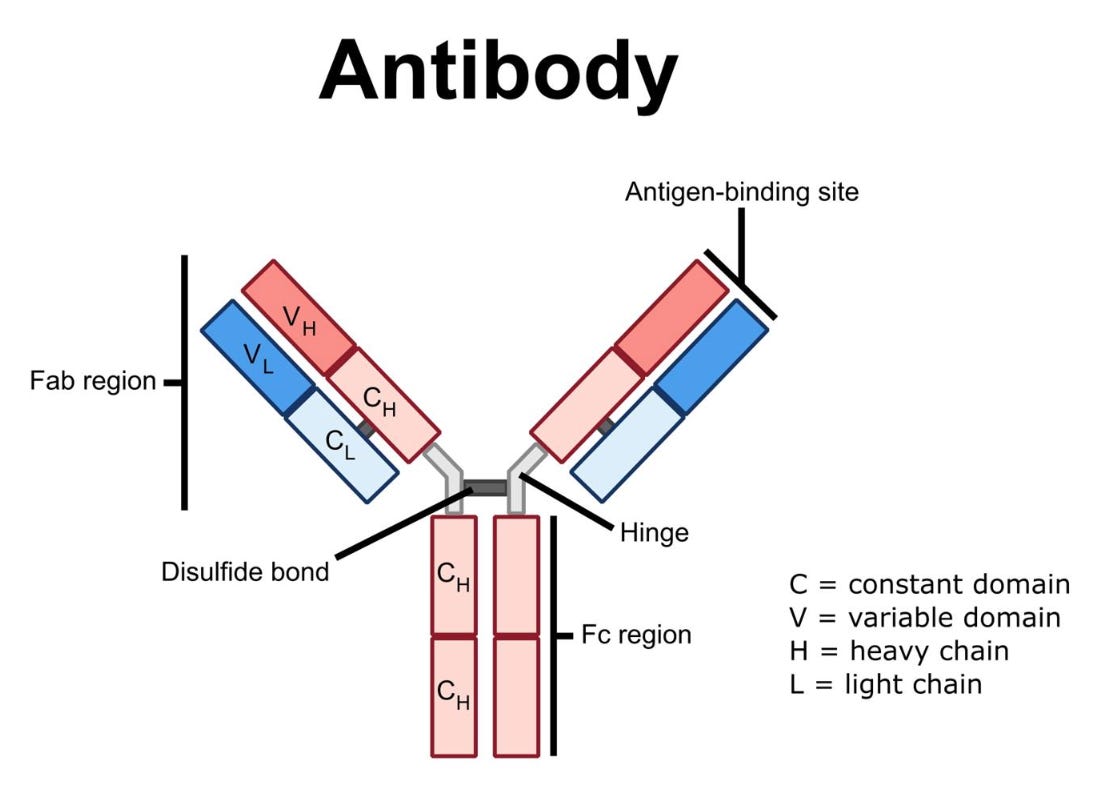

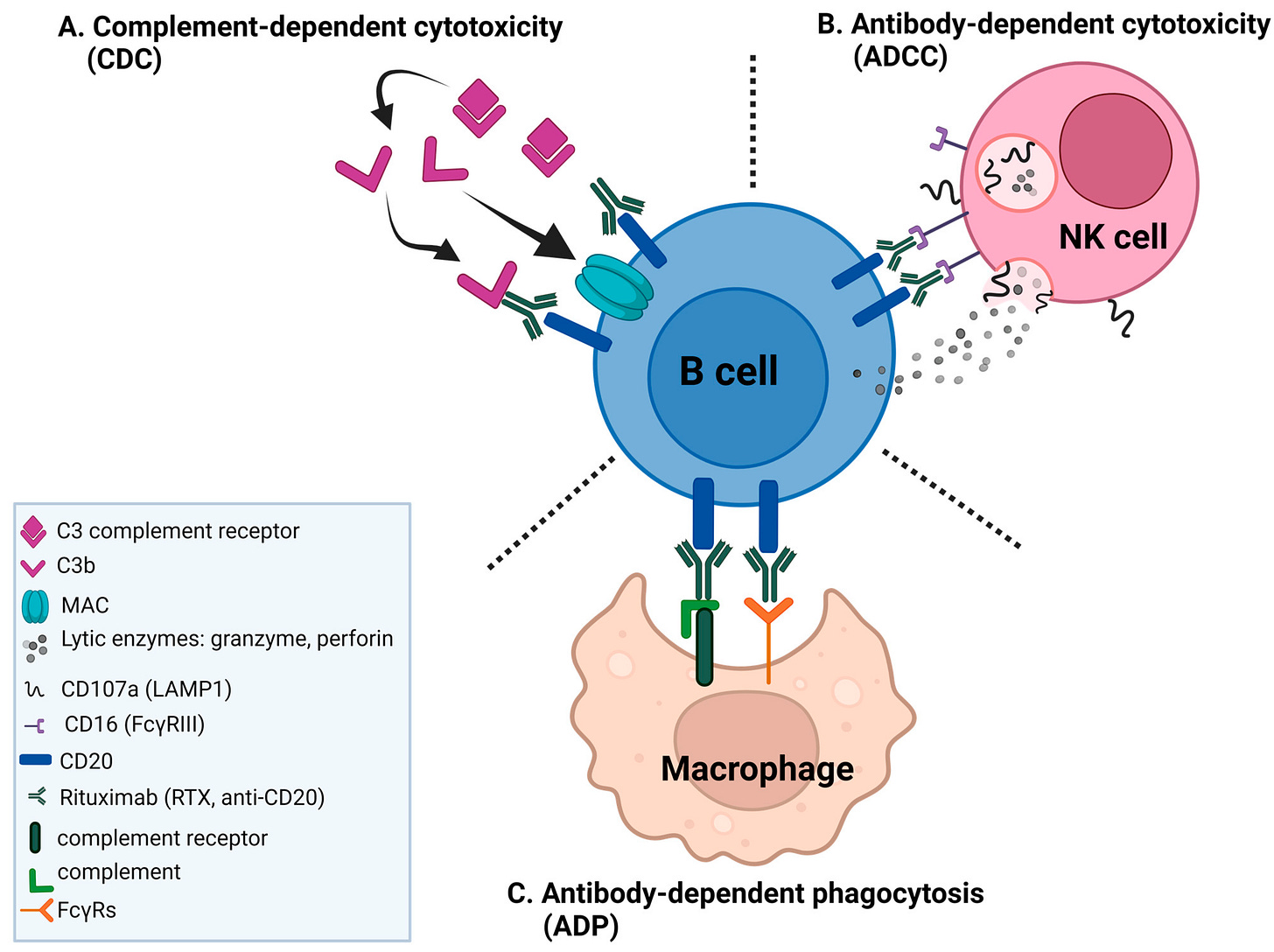

Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity (CDC): The complement system is a collection of extracellular proteins that initially recognize and bind to an antibody’s Fc region (i.e., the highly conserved tail of the “Y” shaped IgG antibody, as shown below). Following antibody recognition, a cascade of complement proteins are recruited and assembled into a membrane attack complex (MAC) that forms pores within the target cell membrane resulting in osmotic imbalance and cell lysis.

Anatomy of an IgG monoclonal antibody. Source Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC): Natural killer (NK) cells are a component of the innate immune system that recognize the Fc region of antibodies via their surface expression of Fc-gamma receptors (FcγRs). When NK cells recognize an antibody-coated B cell, they become activated and release lytic enzymes (i.e., perforin and granzyme) that selectively destroy the target cell.

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis (ADCP): Similar to ADCC, macrophages recognize the Fc region of antibodies through FcγRs. However, instead of lysing the cells, macrophages engulf and digest the target cell in a process called phagocytosis.

Building on the strong clinical success of rituximab, the development of novel modalities for B cell depletion—especially those that engage other immune mechanisms for eliminating cells, such as bispecific T cell engagers (TCEs) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells—has exploded, significantly expanding the treatment landscape for B cell malignancies.

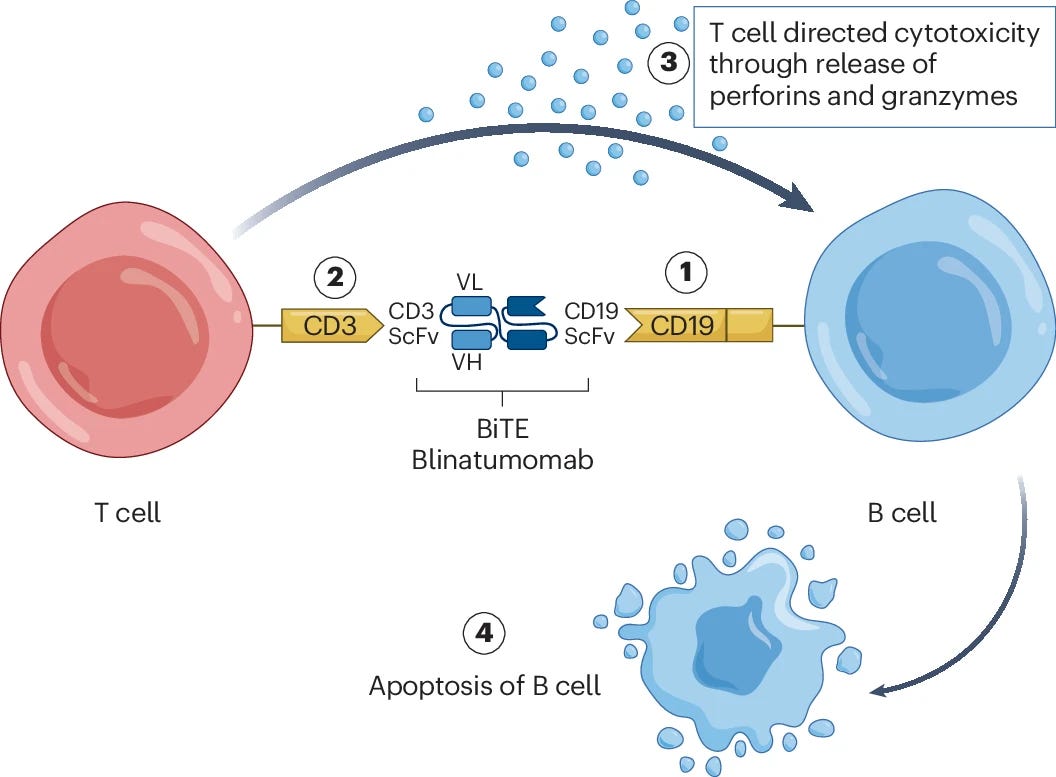

TCEs are often formatted as bispecific antibodies, which are engineered to bind different targets with each arm of the antibody. For example, one arm typically recognizes the CD3 surface receptor specific to T cells, while the other arm recognizes a unique surface marker on the target cell of interest (in the case of BCDTs, CD19 or CD20 on B cells). Upon formation of this molecular bridge, the T cell is activated and subsequently lyses the target cell through release of perforin and granzyme molecules. TCEs bypass traditional antigen presentation to T cells, offering a distinct elimination mechanism compared to mAbs. However, without fine tuned control, TCEs can potentially lead to uncontrolled over-activation of T cells and severe immune-related side effects

Another T cell-centric approach, therapeutic CAR T cells have also shown tremendous curative efficacy for targeting B cell populations. By engineering T cells with a synthetic receptor that binds specific cell surface markers, CAR T cells can selectively eliminate target cells of interest. Similar to TCEs, CAR T cells do not rely on traditional mechanisms of T cell activation and can be tuned to target a wide range of cell types for many disease indications through the modulation of the binding region of the CAR. However, despite their initial clinical success, CAR T cell therapies are often limited by severe safety issues (e.g., cytokine release syndrome), require broad lymphodepletion chemotherapy prior to cell therapy to limit rejection of the CAR T cells, and are gated by poor infrastructure for scalable manufacturing, since these therapies currently require ex vivo culture and engineering.

There is no question that BCDTs have revolutionized the treatment of B cell malignancies. Given their historical success in oncology, there has been considerable growing interest in applying the same approaches to inflammatory and immunology (I&I) indications—particularly autoimmune diseases. But what exactly are autoimmune diseases, what role do B cells play in their pathologies, and why are they promising indications for BCDT?

Autoimmune Diseases

Your immune system comprises several unique cell types responsible for recognizing and eliminating pathogens (e.g., bacteria, viruses, fungi) and diseased cells (e.g., cancer). These immune cells are taught to distinguish between healthy proteins and tissues from your own body (i.e., “self”) versus foreign organisms and diseased tissue (i.e., “non-self”) through highly orchestrated processes called central and peripheral tolerance.

While the processes differ between immune cell types, central and peripheral tolerance can be broken down into two major components:

The elimination of immune cells that target self-antigens on healthy tissue

The maturation of immune cells that correctly recognize foreign antigens

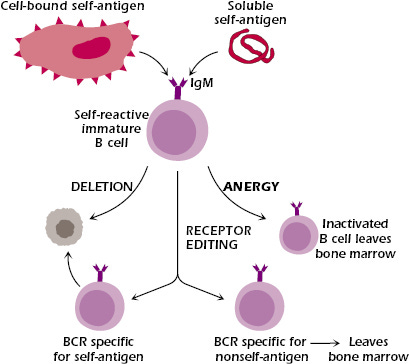

Take B cells, for example—each B cell originates from a unique parent “clone” that expresses a distinct B cell receptor (BCR)—a membrane-bound form of the antibody it secretes. The BCR determines which antigen the B cell recognizes. Upon recognition of its unique antigen, B cells become activated and differentiate into mature states where their primary function is to secrete soluble antibodies to tag and eliminate the antigen.

Before arriving at this mature state, B cells must learn self from non-self. As immature B cells develop in the bone marrow, each clone undergoes a highly intricate process called VDJ recombination, in which variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments rearrange randomly to generate a unique amino acid sequence corresponding to a novel BCR/antibody. These newly formed B cells are then exposed to self-antigens—either in soluble form or presented by neighboring stromal cells. If a B cell’s BCR strongly interacts with a self-antigen, it faces one of three fates:

Apoptosis (i.e., cell death)

Receptor editing via additional rounds of VDJ recombination to form a new BCR

Functional inactivation through a process called anergy, in which the B cell downregulates its BCR and becomes unresponsive

B cell clones that do not bind to self antigens proceed in development and migrate as transitional B cells to peripheral immune organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes. Here, they undergo peripheral tolerance, a second round of negative selection to further ensure they do not react against self-antigens, before becoming fully mature.

Keeping this process in check is central to maintaining healthy cell and tissue function across all organ systems. To put this into perspective, the human body contains ~2 trillion lymphocytes—including T cells, B cells, and NK cells. That’s ~2 trillion cells that must be correctly taught to recognize friend or foe. If even a single lymphocyte escapes this education process without proper regulation, it may mistakenly recognize the body’s own proteins as foreign. This breakdown of central tolerance can occur due to a variety of factors including genetic predisposition and environmental factors that impact the negative selection process as well as loss of regulatory immune cell populations that limit proliferation of auto-reactive clones. This misdirected immune response triggers an attack on healthy tissues, leading to progressive damage and loss of function—the hallmark of autoimmune disease.

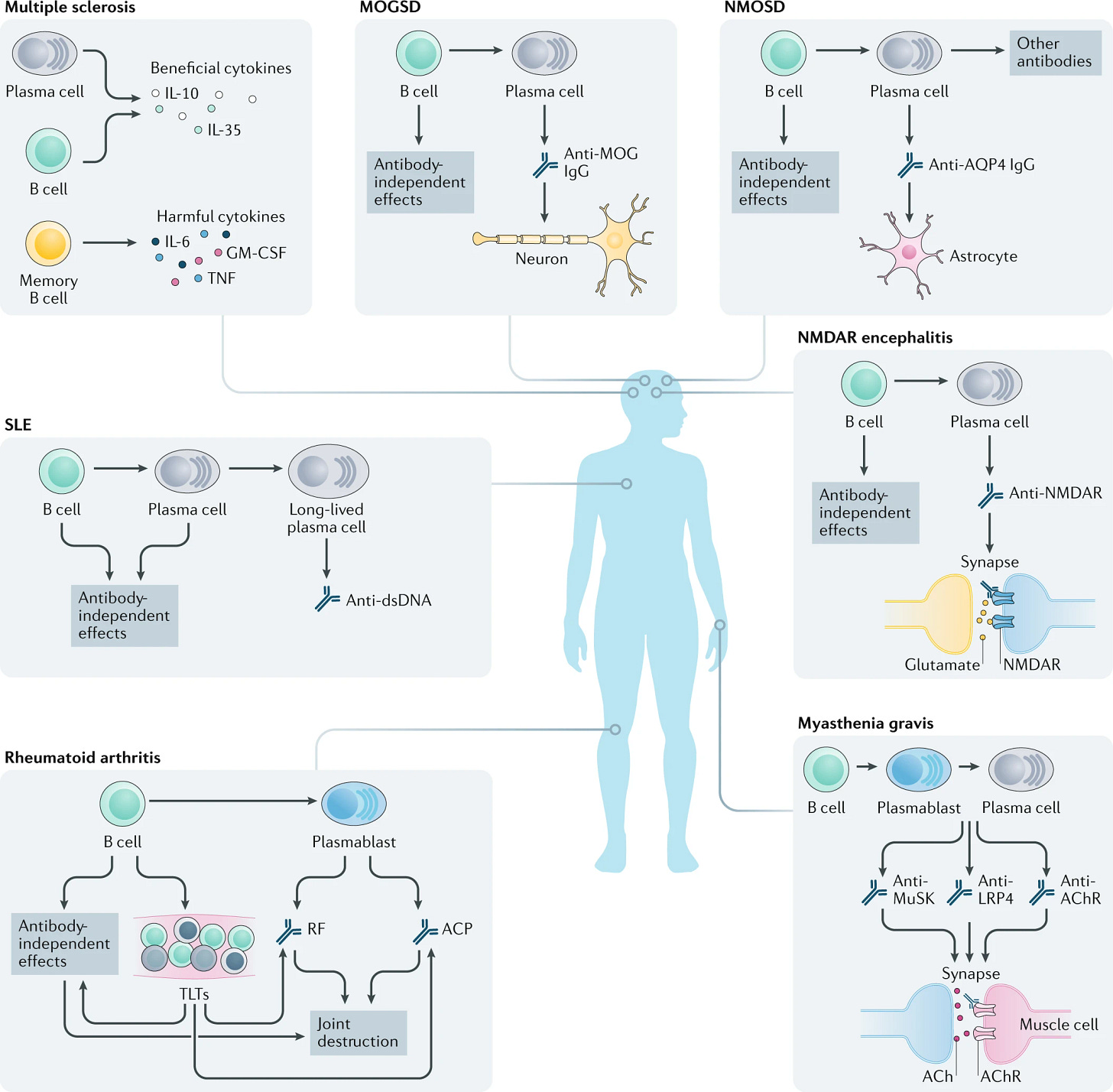

Autoimmune diseases encompass a broad spectrum of disorders, which are usually categorized by tissue type and disease mechanisms. Some of the most common examples include psoriasis, multiple sclerosis (MS), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), type 1 diabetes (T1D), and systemic lupus erythematous (SLE).

The rise of autoimmune diseases, their burden on the healthcare system, and the need for innovative therapies is becoming increasingly apparent. A recent study in The Lancet showed that autoimmune diseases affect an estimated 1 out of 10 individuals during their lifetime. In the United States, it is estimated that over $100 billion dollars are spent every year on healthcare costs for patients with autoimmune diseases.

Current Autoimmune Treatments and Emerging Cell Depletion Approaches

Historically, autoimmune diseases have been predominantly treated with anti-inflammatory medications that work to broadly suppress the dysregulated immune system (e.g., corticosteroids and non-steroidal drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen).

Recently, more targeted therapies that block specific pro-inflammatory factors have been approved for clinical use, including small molecule inhibitors of JAKs (e.g., tofacitinib, upadacitinib) and mAbs against pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL6, and IL17 (e.g., adalimumab, tocilizumab, secukinumab).

Despite often demonstrating greater efficacy, these newer therapies have yet to universally replace traditional broad immunosuppressants as first-line (1L) treatments for autoimmune disease. This could be due to a mixture of increased side effects, long-term safety concerns, higher costs, and the entrenchment of well-established standard of care treatments. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and broad disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate are typically the 1L treatments for severe disease. Meanwhile, TNF-α inhibitors and other biologics are usually reserved for patients who do not respond to initial therapies.

Though precision drugs have led to improvements in quality of life and a more controlled rate of disease progression in patients, they primarily function by dampening inflammation rather than addressing its underlying causes. Toward this goal—cell depletion therapies are beginning to gain traction.

Borrowing from BCDTs in oncology, the idea here is that if you can identify the cell type(s) driving autoimmune pathology, you can leverage targeted therapeutic strategies to selectively eliminate (i.e., deplete) them, thus permanently halting disease progression.

However, the root causes of these diseases and the mechanistic roles different immune cell types play are often not well understood, making it difficult to design effective therapies. Historically, T cells have been considered the predominant driver of autoimmune diseases due to their innate cytotoxic activity. For example, in Type I Diabetes, auto-reactive T cells target and destroy healthy beta cells in the pancreas, leading to decreased insulin production and disease onset.

As a result, broad T cell depletion therapies have been explored for the treatment of autoimmune disease but have faced considerable challenges. One major concern is the substantial safety risk associated with the broad depletion of T cells, which are essential for immune surveillance and defense against infections and malignancies.

Additionally, T cell maturation and central tolerance occur in the thymus, an organ that begins to shrink rapidly after the first year of life. Consequently, older patients face greater difficulty repopulating their immune system following T cell depletion, leading to diminished tolerance and a less diverse and functional T cell repertoire, which may impair their ability to respond to infections and even contribute to the onset of additional autoimmune diseases.

In light of these challenges with broad T cell depletion, researchers have looked to other immune cell types, such as B cells, whose contribution to autoimmune disease phenotypes is growing in appreciation.

In several autoimmune diseases, B cells become dysregulated and contribute to the breakdown of immune tolerance (i.e., your immune system’s ability to recognize a self antigen and not mount a response). For example, an auto-reactive B cell clone that snuck through negative selection processes will secrete “autoantibodies” that recognize self antigens on healthy tissue, marking them for elimination.

Additionally, in autoimmune diseases, B cells may upregulate expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that further drive the misguided attack on healthy tissues. This upregulation can be driven by several factors including metabolic dysregulation and loss of B regulatory cells—a subpopulation responsible for suppressing inflammation though secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, leveraging BCDT to selectively eliminate these diseased B cells could alleviate the root causes of many autoimmune diseases. But what happens once some or all of your B cells are eliminated?

In contrast to other immune cell types (e.g., T cells), B cells are ideal targets for cell depletion therapy due to their ability to repopulate over the course of a person’s lifetime. Specifically, B cells are continuously differentiated from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow, ensuring a constant supply of naïve clones capable of responding to novel antigens. This allows the B cell population to effectively “reset” following treatment, resulting in a more self-tolerant state and permanently removing auto-reactive B cell clones. However, B cell repopulation is poorly understood and difficult to regulate, which poses a risk to the successful reestablishment of a healthy immune system for patients following treatment.

Translation from Oncology to Autoimmune

Given the shared goal of depleting pathogenic B cell populations, the I&I field has increasingly taken a “copy and paste” approach—directly repurposing successful oncology assets for autoimmune treatment. While most BCDTs for autoimmune disease treatment remain in preclinical development or early clinical trials, a handful of late-stage drugs are showing promise.

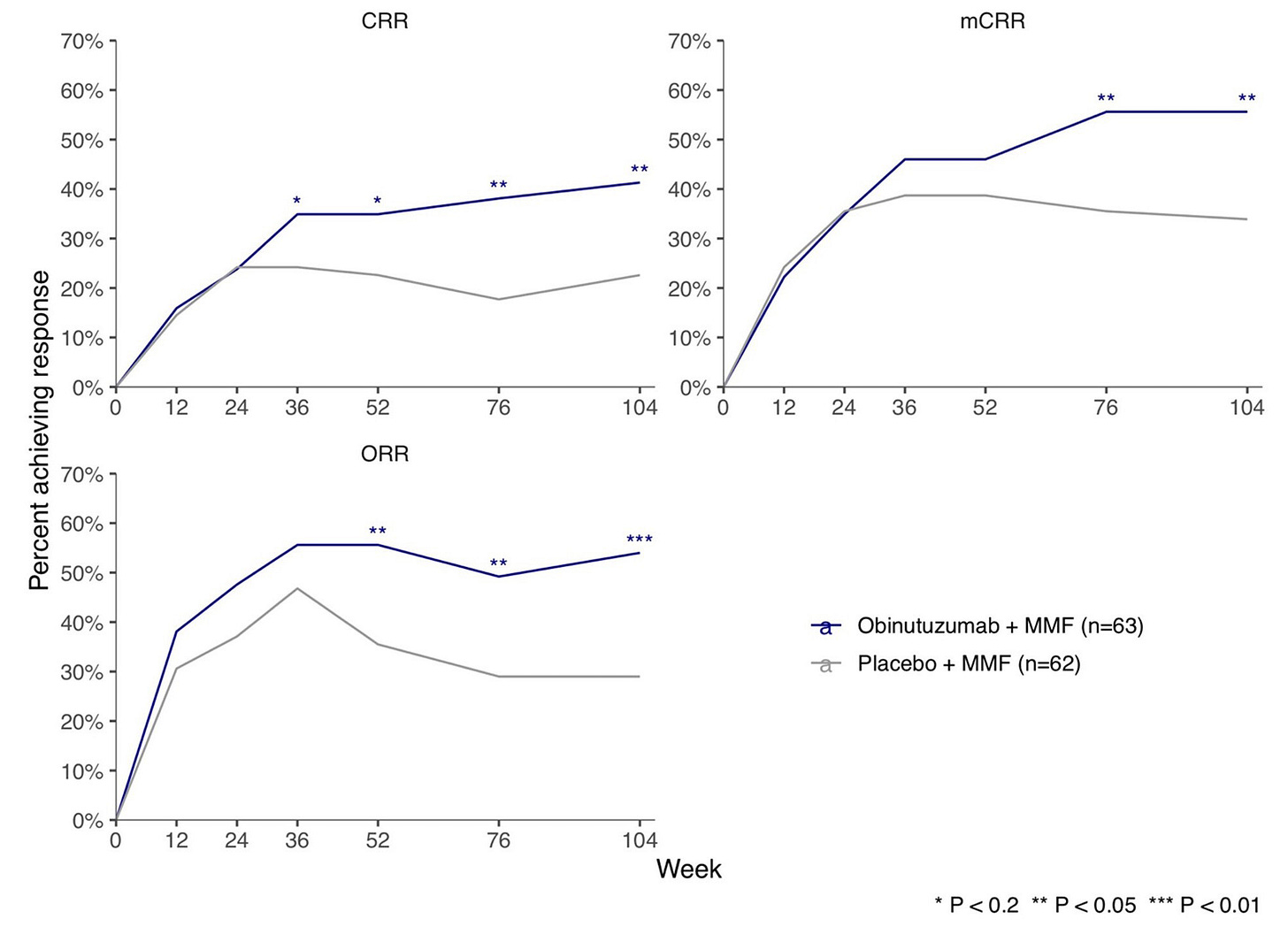

Given that small molecules and mAbs were some of the first modalities to gain clinical approval for BCDT in oncology, it’s no surprise they are leading this first wave of autoimmune BCDTs with a few assets approaching clinical approval. In particular, Roche/Genentech has made significant progress in translating their CD20 mAb (obinutuzumab) for the treatment of lupus nephritis, recently sharing positive Phase III clinical trial results. Additionally, Roche also showed that small molecule inhibition of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) with fenebrutinib led to near-complete disease remission in MS patients in a Phase II trial. BTK is a target approved for clinical treatment of B cell lymphomas and is necessary for B cell survival and maturation.

There is growing momentum as these small molecules and mAbs are followed closely by bispecific antibody TCEs and CAR T cell therapies. For example, Roche has several early ongoing trials for TCEs including a Phase I trial testing mosunetuzumab (an approved oncology drug targeting CD20 x CD3) for the treatment of SLE. Additionally, Curon Biopharmaceuticals and their CD3 x CD19 bispecific antibody CN201 was recently acquired by Merck in Oct 2024 for $750M. CN201 is currently being tested in Phase I and Ib/II clinical trials for B cell malignancies with an opportunity for expansion into autoimmune diseases.

On the cell therapy front, CD19 has been the predominant target for CAR T cell treatments for B cell malignancies. In particular, Kyverna Therapeutics is at the forefront of translating CD19 CAR-T therapy for the clinical treatment of autoimmune diseases, currently conducting Phase I/II and Phase II trials across several indications.

As these trials progress, we anticipate some will show meaningful clinical success for autoimmune patients. However, directly translating oncology assets to autoimmune patients comes with some considerable roadblocks. The biggest hurdle lies in the substantial difference in risk tolerance and safety thresholds across these patient populations, mainly driven by key biological and clinical differences. While immediately life-threatening diseases like late-stage cancer may justify the use of therapies with lower or unproven safety profiles, chronic autoimmune conditions will require safer therapeutic approaches.

Take diffuse large B cell lymphoma, for example. If left untreated, patients have a median survival of < 1 year, making the need for rapid therapeutic intervention high and the bar for therapeutic safety low. For patient populations like this, the primary goal for BCDTs has been maximizing B cell depletion by targeting cell surface markers expressed across a broad population of B cell subtypes (e.g., CD19, CD20). But this broad approach to depletion comes at the price of safety, specifically increased risk of infections and the onset of cancer. One could argue that because B cells naturally repopulate, this safety issue should only be a temporary. However, B cell repopulation is generally an understudied, uncontrolled process - often taking months to years - only to result in B cells skewed towards an immature phenotype.

In our view, safely restoring the B cell compartment to a healthy baseline remains one of the largest bottlenecks for the safe clinical translation of broad cell depletion therapies for I&I diseases.

If BCDTs are going to live up to their curative potential and become widely adopted for autoimmune diseases, their target product profiles will need to evolve to a point where safety is prioritized alongside efficacy. With this in mind, two major questions drive this cost/benefit between efficacy and safety of autoimmune BCDTs:

What therapeutic modalities are uniquely suited for these patients?

If broad depletion of B cell subtypes poses too great of a safety risk, what B cell subpopulations are the most relevant to target and can we actually target them via cell-specific markers?

Spotlight on T Cell Engagers for Autoimmune

TCEs offer several key advantages over other therapeutic modalities for BCDTs. For example, given they are often formatted as IgG based antibodies—TCEs are already clinically de-risked. They benefit from high selectivity and specificity toward their target antigen, relatively high stability, predictable pharmacokinetics, favorable safety profiles, general ease of manufacturing, and result in a final “off-the-shelf” product. These attributes set a strong foundation for TCEs, where they can thread the needle between achieving solid efficacy while limiting severe safety issues.

While potentially exciting, TCEs for treating autoimmune diseases via B cell depletion still have therapeutic hurdles to overcome in the race to clinical approval.

Current clinical data show that mAb and TCE therapies can achieve deep depletion of B cells circulating in the blood. This makes sense given these drugs are most often delivered intravenously, and in itself, this depletion can have a strong impact on disease state. However, the field is also beginning to appreciate the important roles of tissue-resident subpopulations of B cells in driving disease phenotypes. For example, auto-reactive, tissue-resident memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells, both of which produce autoantibodies, are commonly associated with disease persistence and relapse. Unfortunately, IgG-based TCEs are relatively large (~150kDa) molecules that have limited tissue penetrance, making it difficult to access and deplete these tissue-resident cell types. Alternative TCE formats based on the linkage of smaller scFv’s—often referred to as bispecific T cell engagers (BiTES)—may improve deep tissue penetrance, but this approach has so far come at the cost of plasma stability.

Another potential limitation with TCEs is that they require the presence of endogenous effector T cells to enable target cell depletion. While we’ve not seen particularly strong evidence that this will be a significant issue for autoimmune diseases, it may be a consideration for patients who have previously undergone broad lymphodepletion treatment.

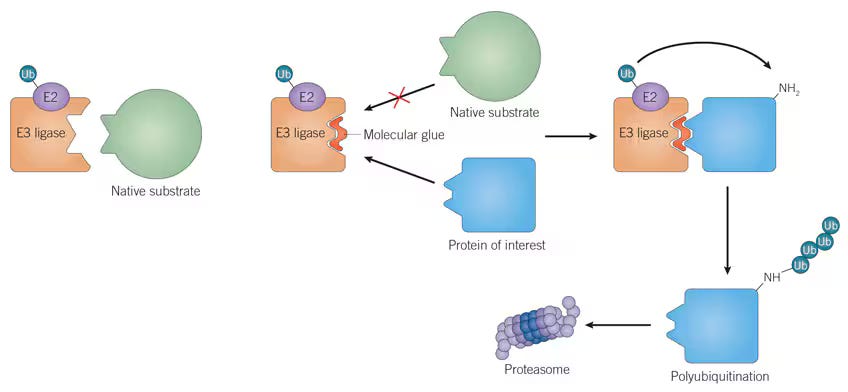

There’s a loose parallel here to molecular glues. Molecular glues are small molecules that stabilize interactions between an E3 ligase and a protein targeted for degradation. Upon binding, the E3-E2 ligase complex appends a ubiquitin tag onto the target protein, marking it for recognition and degradation by the proteasome. Just as BCDTs rely on the presence of endogenous effector T cells, the effectiveness of molecular glues is also constrained by the availability of specific E3 ligases and their associated degradation machinery, which can severely limit the versatility of these therapies across cell and tissue types, as shown below.

Initial clinical results for TCEs for the treatment of autoimmune disease are beginning to roll in. A 2024 Phase I study of blinatumomab (a CD19 x CD3 BiTE) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis showed promising safety results, a decrease in autoantibody serum levels, and a decrease in clinical disease activity across a cohort of six patients.

Commercialized by Amgen, blinatumomab was the first FDA-approved bispecific and TCE. It originally received accelerated approval in 2014, followed by full approval in 2018 for the treatment of leukemia. While the above study is limited by a small patient cohort, blinatumomab was shown to deplete B cells and improve disease symptoms in patients who previously failed rituximab treatment, suggesting TCEs may be able to overcome efficacy issues faced by some traditional mAb-based cell depletion therapies.

Targeting the Right B Cell Subpopulation

Layered on top of the therapeutic modality question is the B cell subpopulation question. Should drug developers aim for a more complete reset of the entire B cell compartment through the depletion of all B cell subtypes, similar to the traditional oncology approach? Or, would a more selective strategy be better, where specific pathogenic B cell subtypes or even specific auto-reactive clones are targeted, while sparing the rest of the population? As the saying goes—it depends.

The decision to mount a broad versus targeted approach to BCDT ultimately depends on our understanding of the underlying causes of each autoimmune disease. For the sake of this discussion, we can compartmentalize autoimmune diseases into two main categories: (a) complex diseases where the mechanistic roles of B cells and other immune cell types in driving disease pathology is still poorly understood, and (b) B cell-mediated diseases that are largely driven by the aberrant production of autoantibodies targeting healthy tissue antigens.

If we don’t fully understand the underlying disease mechanisms of complex autoimmune diseases such as RA, MS, and SLE, designing effective targeted therapies is nearly impossible. For now, broad B cell depletion strategies may actually be the most effective treatment options available. Of course, this approach does come with safety concerns associated with poor repopulation dynamics and risk of permanent immunosuppression; however, we are learning how to manage these side effects from initial attempts in oncology. Specifically, both re-vaccination and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) injection to restore protective immunity, have helped to alleviate patient side effects.

Beyond their therapeutic benefit, broad depletion approaches like these also provide an opportunity to gain valuable insights into autoimmune disease mechanisms. By carefully analyzing patient responses to BCDT and the dynamics of B cell repopulation, we can deepen our understanding of complex immune processes, which in turn can help us develop more targeted therapies in the future.

For autoimmune diseases that are primarily driven by autoantibody-producing plasma cells, a more targeted approach may be optimal. For example, in pemphigus vulgaris, autoantibodies specifically target cell-cell adhesion proteins called desmosomes in the skin (DSG1 and DSG3), while in myasthenia gravis, autoantibodies specifically target muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) present in cells at neuromuscular junctions.

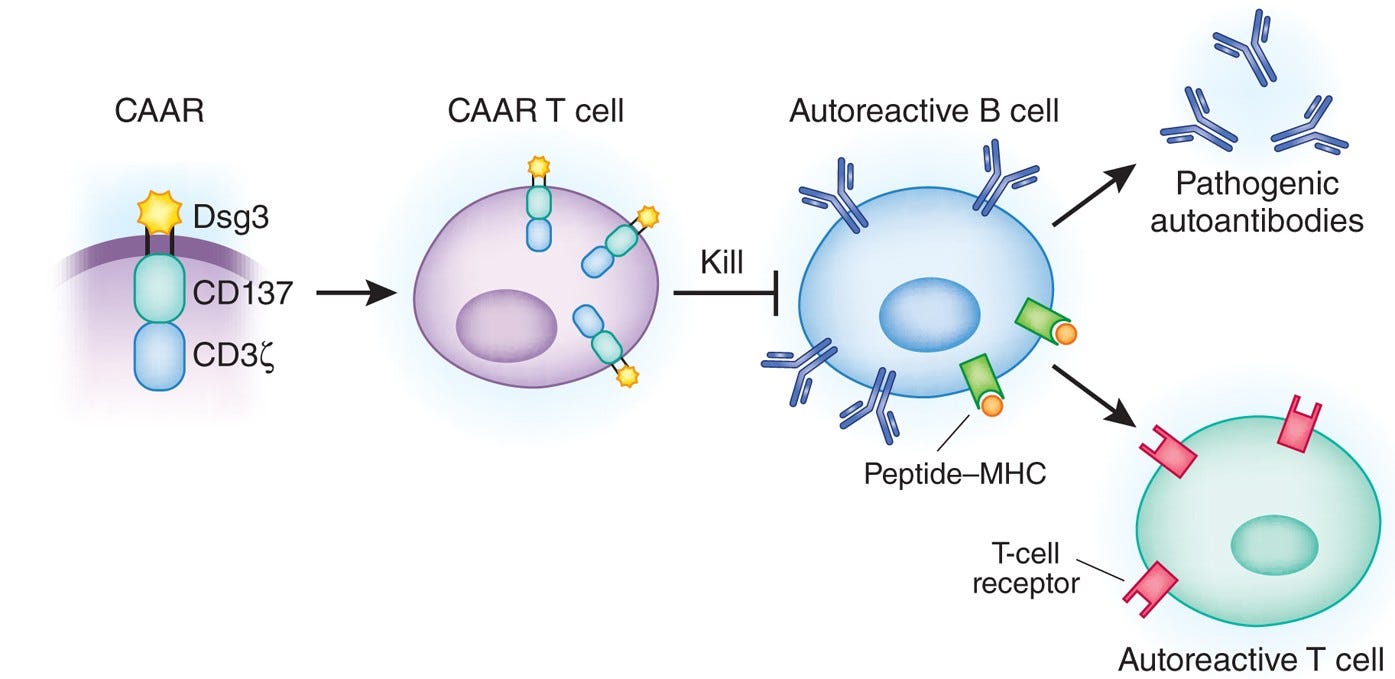

Given these well-defined and disease-relevant targets, researchers have developed modified versions of BiTEs and CAR T cells that leverage auto-antigen recognition to selectively eliminate only the plasma cell clones responsible for autoantibody production. These therapies—termed bispecific autoantigen-T cell engagers (BiAATEs) and chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR) T cells—flip the script on conventional molecular design of BiTEs and CAR T cells.

Take BiAATEs, for example. Instead of using an antibody or scFv to target broad B cell markers such as CD19 or CD20, BiAATEs present a disease-specific auto-antigen to selectively target auto-reactive plasma cells. This auto-antigen is recognized only by the particular plasma cell clone with the corresponding auto-reactive BCR / autoantibody.

By linking the auto-antigen to an anti-CD3 domain, BiAATEs recruit cytotoxic T cells to eliminate the auto-reactive plasma cell in the same manner as a traditional TCE. The same principle applies to CAAR T cells, where the conventional scFv targeting a cell surface antigen is replaced with an auto-antigen to enable precise, clone-specific killing.

Dialing in the optimal specificity for each autoimmune disease will be critical to achieving curative therapies with tolerable side effects. For example, these more targeted therapies will also spare regulatory B cells, a subset of B cells that are inherently immunosuppressive and contribute to alleviating autoimmune symptoms. Regulatory B cell depletion has been linked to worsened disease severity in some autoimmune conditions, making this a critical factor in designing safer and more effective BCDTs.

As our understanding of disease mechanisms inevitably grows, we believe BCDTs will also evolve towards targeting more distinct subpopulations, maximizing efficacy while minimizing off-target effects.

Current BCDT Outlook

The treatment landscape for autoimmune and other I&I diseases is poised for a major transformation. In our view, BCDTs are a critical part of the future of I&I disease treatment with several advantages over other therapeutic strategies:

Curative Potential: Unlike other approved therapeutic options that rely on broad immunosuppression, BCDTs target underlying autoimmune mechanisms, offering the potential for more durable remission and even curative outcomes.

Therapeutic Flexibility: The wide range of therapeutic modalities being explored for BCDTs increases the extracellular and intracellular target space for the precise targeting of specific B cell subpopulations, enabling more effective treatment options for patients. For example, small molecule BTK inhibitors enable targeting of a unique intracellular kinase important for B cell survival, while antibody-based therapeutics (e.g., TCEs) enable selective recruitment of cytotoxic T cells to the target cell of interest based on expression of extracellular surface receptors.

Broad Applicability: Given the central, mechanistic roles of B cells in driving inflammatory disease pathology, BCDTs have the potential to treat a wide range of autoimmune and I&I patients.

Reduced Off-Target Risks of Broad Immunosuppression: BCDTs are designed to target specific B cell populations while preserving other immune cell types. While there are still considerable safety concerns that need to be addressed with BCDTs, keeping the rest of the immune system intact can help to reduce risk of severe infections and disease onset compared to broad immunosuppression.

Over the next decade, we expect to see frontline treatments shift from broad systemic immunosuppression to precise immune modulation and long-term remission. We are quite excited for the future of cell depletion therapies and the benefits they will bring to patients. If you have any thoughts or opinions on the field, feel free to send me a message!