On the Foundations of Machine Reasoning

Our effort to imbue machines with human-like cognition is fledgling, leaving today’s AI systems in an uncanny valley. Will they emerge with preternatural reasoning or remain mirages of intelligence?

Introduction

It’s in the name—artificial intelligence (AI). Since the 1956 AI conference at Dartmouth, researchers have sought to install aspects of the human mind—perception, logic, reasoning—into machine systems.

Humans and computers are more alike than we’d like to admit. We are both complex input-output devices. Our brains react to stimuli, triggering a cascade of electrical and chemical impulses that results in thought or action. Computers do the same, though they exchange our spongiform gray matter for squared-off silicon conduits.

What happens between that initial stimulus and the observed output—that’s where the major differences reside. It’s also where the frontier of machine learning (ML) research is focused. By encouraging ML algorithms to think as we do rather than simply parroting the underlying data distribution of their training corpora, can we approximate a human mind—or something even more powerful?

Table of Contents

A New Scaling Paradigm

“…post-training methods [like reinforcement learning] and the burgeoning field of test-time scaling (TTS) prove that some form of inductive human bias…is general enough and powerful enough to enable discontinuous leaps in LLM performance…”

Recently, we summarized the first era of large language model (LLM) scaling. Pretraining LLMs with an empirically-determined recipe of tokens, parameter counts, learning rates, and GPU-compute unlocked years of monotonic performance gains. Unfortunately, those halcyon days are rapidly fading.

We’ve run up against several pretraining limits. The multi-year digital fracking campaign has exhausted the Earth’s pretraining token supply. Turning the pretraining crank on trillion-parameter LLMs requires a nation-state’s monetary, energy, and cooling resources. Even worse, performance was showing evidence of diminishing returns.

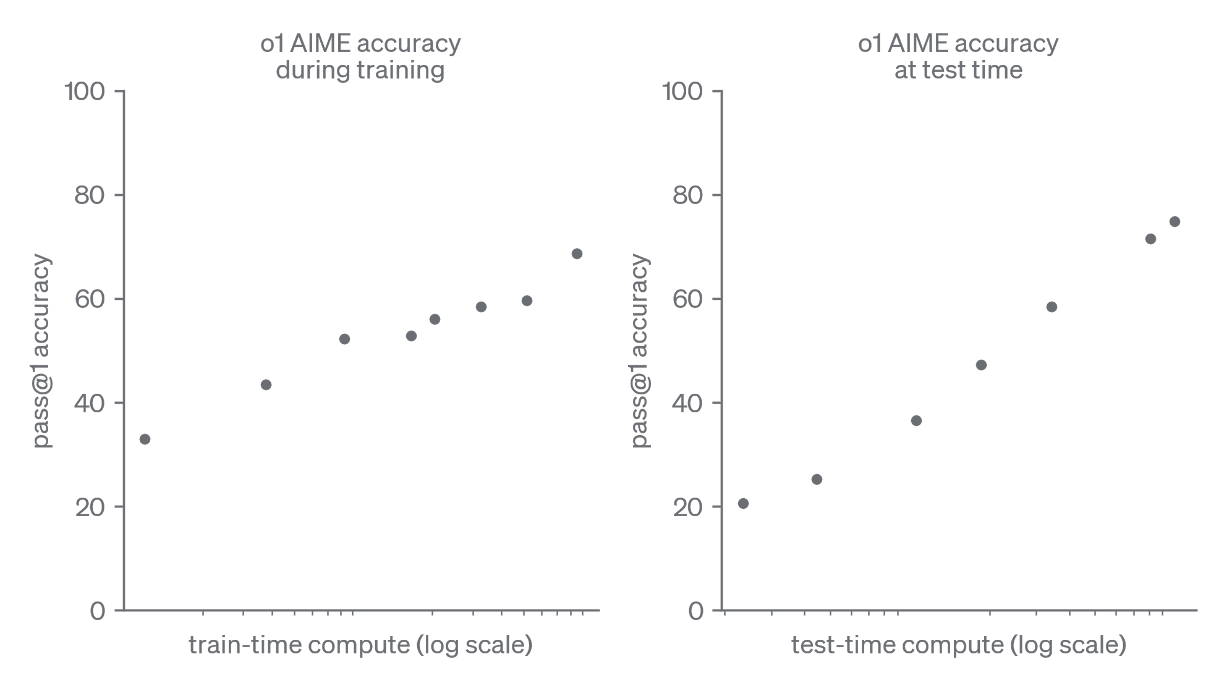

The Bitter Lesson—that general ML methods leveraging scale outperform those with brittle human heuristics—is still alive and well. However, it’s being refined. Contemporary post-training methods (e.g., reinforcement learning, RL) and the burgeoning field of test-time scaling (TTS) prove that some form of inductive human bias—like the way we think—is general enough and powerful enough to enable discontinuous leaps in LLM performance compared to brute-force pretraining, as shown below by OpenAI.

Clearly, pretraining was never the endgame. Consider that children are exposed to an average of fifty-million tokens during their formative years, yet are capable of abstract reasoning that outstrips today’s frontier LLMs pretrained on >300,000X more data. In fairness, humans benefit from massively parallel sensorimotor input, ingrained inductive priors, and stark learning algorithm differences that preclude an apples-to-apples comparison. Will chipping away at these differences via post-training or other techniques imbue machines with human-level reasoning capabilities?

Thinking Machines

“While many describe the current state of machine reasoning as a mirage, a perverse pantomiming of one of our foundational mental capabilities, the data tell a clear story.”

Goals are impossible to reach unless clearly defined. We cannot judge a machine’s ability to reason without first defining what reasoning is. The blended cognitive science definition is that reasoning is a process of drawing conclusions based on prior information. In his bestseller Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman contrasts fast-twitch, autonomic System 1 thinking with System 2—a slow, deliberate, cognitively-burdensome thinking process.

Beyond academic definitions, humans have a visceral relationship to the reasoning process. Abstract reasoning and indeed metacognition—reasoning about reasoning—are some of the few razors humans use to draw a boundary line between our collective biomass and the rest of the cold, unthinking universe. Several Nebula Award-winning science fiction authors, like Isaac Asimov and Frank Herbert, have described how once-allied thinking machines evolve metacognitive abilities, ultimately revolting against their human creators.

Emulating human reasoning is a prerequisite for achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI)—a form of machine intelligence that matches or exceeds human cognitive abilities across diverse domains. Between now and then—assuming “then” will happen—reasoning models are valuable by themselves.

Reasoning models are more auditable—in part because we have specifically designed them this way. Human inspectors can see how an LLM reaches its output, potentially enabling interpretability of data features that we’ve only barely come to understand ourselves. We can catch errors in reasoning steps to understand why a model fails.

Reasoning models are more general. Instead of pattern-matching to an extant dataset, models capable of logical extrapolations can potentially succeed at out-of-distribution problems, ones that human experts wrestle with daily.

Reasoning models are more economical. A robust, digital reasoning system capable of approximating human-level expertise can inexpensively solve problems that would be too costly for humans to do, potentially shifting human-expert work from doing to monitoring systems that do.

We are mid-flight on our journey to anthropomorphize LLMs with facets of human reasoning. This essay deals with the stepwise transference of the atomic units of human cognition into LLMs—from elementary chains-of-thought to the digital-embodiment of mental exertion with test-time scaling (TTS).

While many describe the current state of machine reasoning as a mirage, a perverse pantomiming of one of our foundational mental capabilities, the data tell a clear story. Inciting something that looks like reasoning via post-training and TTS provides material performance gains on complex, multi-step problems and, as of now, show no signs of slowing down.

Whether mimicking reasoning IS reasoning is a metaphysical conversation that has equal place at late-night cocktail parties just as much as early-morning C-suite strategy meetings. Either way, the march towards AGI via the road of reasoning carries on—and we do our best to survey it here.

Foundations of Machine Reasoning

“Next-token prediction isn’t the way humans think, let alone reason through complex problems.”

Google’s 2017 introduction of the transformer architecture spawned a machine learning revolution. Similar to C-3PO from Star Wars, the transformer was originally built to translate between languages—though perhaps not over six-million forms of communication.

During pretraining, transformers learn the associations and statistical interdependencies between tokens. At inference time, transformers leverage these learned probabilities to predict the next token in a sentence—generating shockingly fluent outputs.

Next-token prediction isn’t the way humans think, let alone reason through complex problems. This is one reason why previous LLM iterations struggled with multi-step, algorithmic calculations, such as GPT-3’s inability to consistently add numbers greater than three digits.

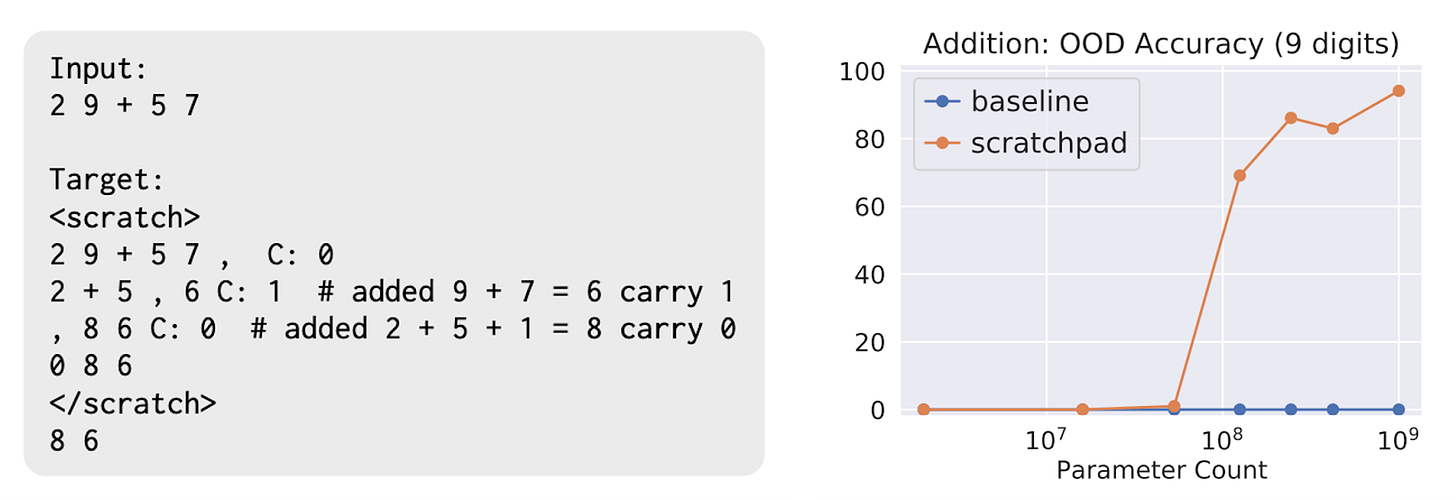

Several years ago, multiple research groups tried to imbue LLMs with the ability to negotiate challenging problems through a series of intermediate steps. Children are taught this early in life. We’re taught to carry-the-one when adding large numbers. This heuristic eases cognitive burden—splitting apart short-term memory from computation. We cannot hold all intermediate states in our minds—we must externalize them and think in chunks.

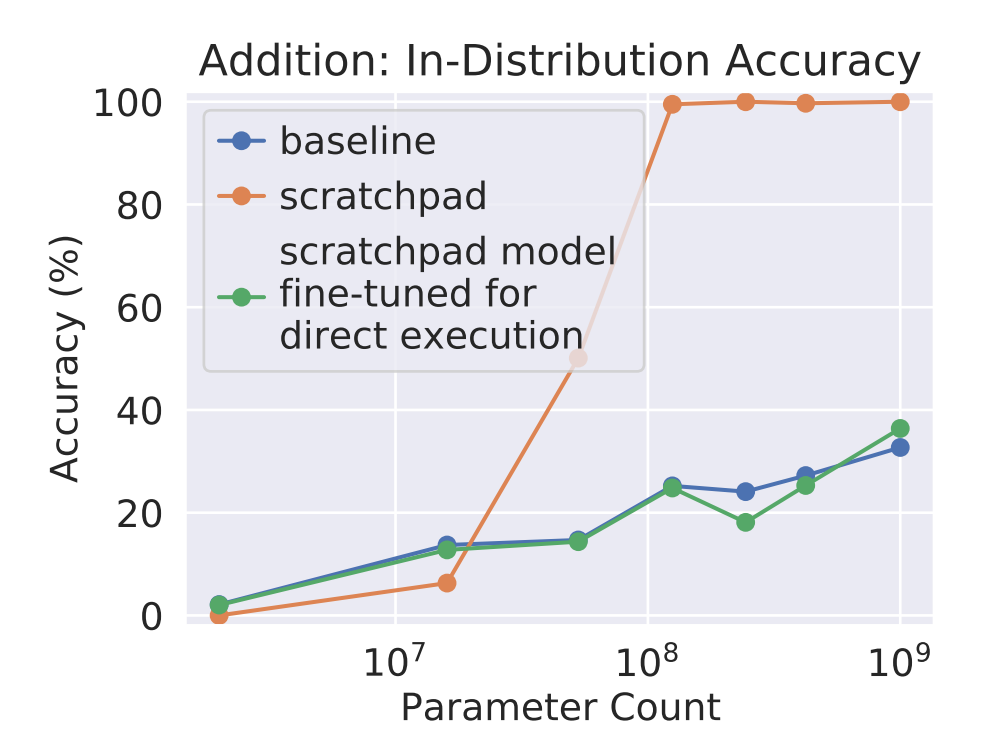

Nye et al. showed in 2021 that doing supervised fine-tuning (SFT) with a 100,000-member library (i.e., a scratchpad) of fully worked out addition problems could boost an LLM’s performance. Essentially, the researchers sat an LLM at the front of the class for a private, long-addition tutoring session with step-by-step examples. Following a gradient update, the model was prompted to produce intermediate steps and the computed output. Interestingly, this technique only had an effect on base models above a certain size, as plotted below.

The paper ends with a fascinating ablation experiment. They first perform SFT with the fully-worked scratchpad, then do a second round of fine-tuning to force the LLM to once again give a direct answer. The results suggest that merely injecting worked long-addition problems is insufficient to drive performance—intermediate steps need to be generated at inference time. Similarly, a student who knows but doesn’t use the heuristics of long-addition will underperform on an exam.

The Missing Link: Chain-of-Thought

“Singular, in-context reasoning traces offer a more economical and generalizable alternative to enhance LLM reasoning capabilities—or at least the semblance of reasoning.”

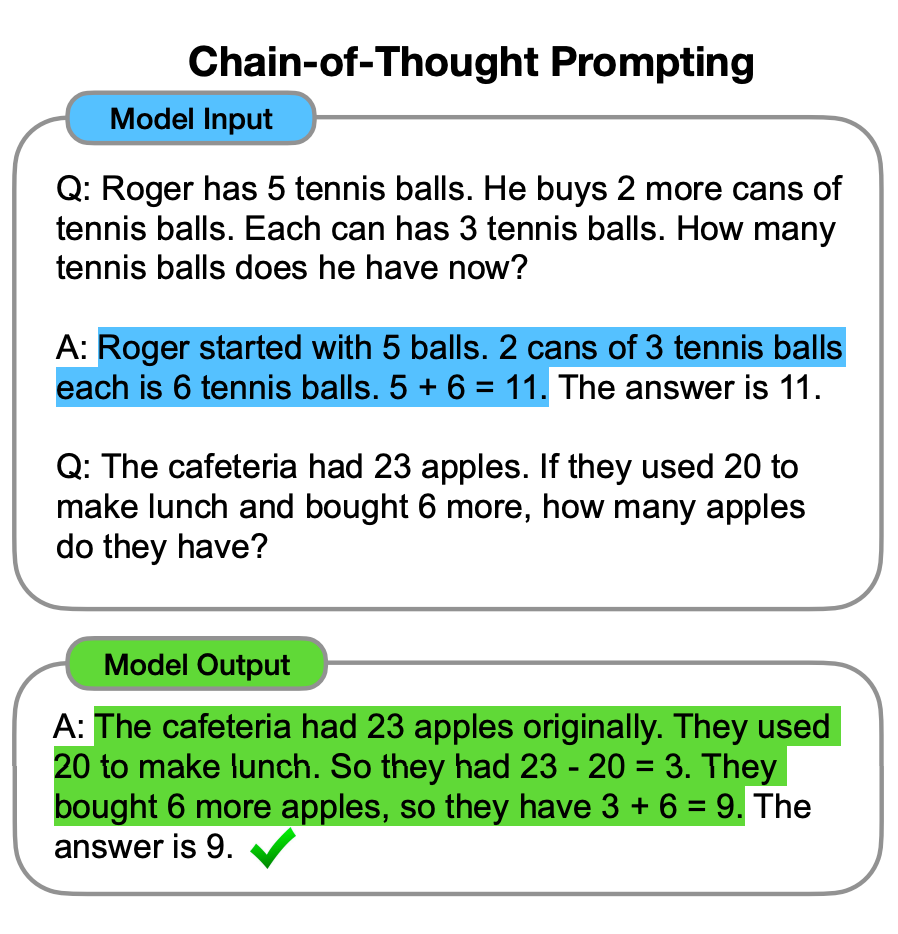

Contemporary LLMs are more akin to precocious students, prompting a second group of Google researchers to ask whether a model can achieve high performance without attending extensive tutoring sessions (i.e., SFT). Instead, they provided a pretrained LLM with a within-prompt example—an {input, rationale, output} tuple—providing a reasoning scaffold that the model would follow to generate a chain-of-thought (CoT) at inference time.

Expert tutors are expensive, especially if they need to generate 100,000 solved examples for a student to learn. Fine-tuning libraries may also be brittle, unable to help students in problem domains dissimilar from the training set. Singular, in-context reasoning traces offer a more economical and generalizable alternative to enhance LLM reasoning capabilities—or at least the semblance of reasoning.

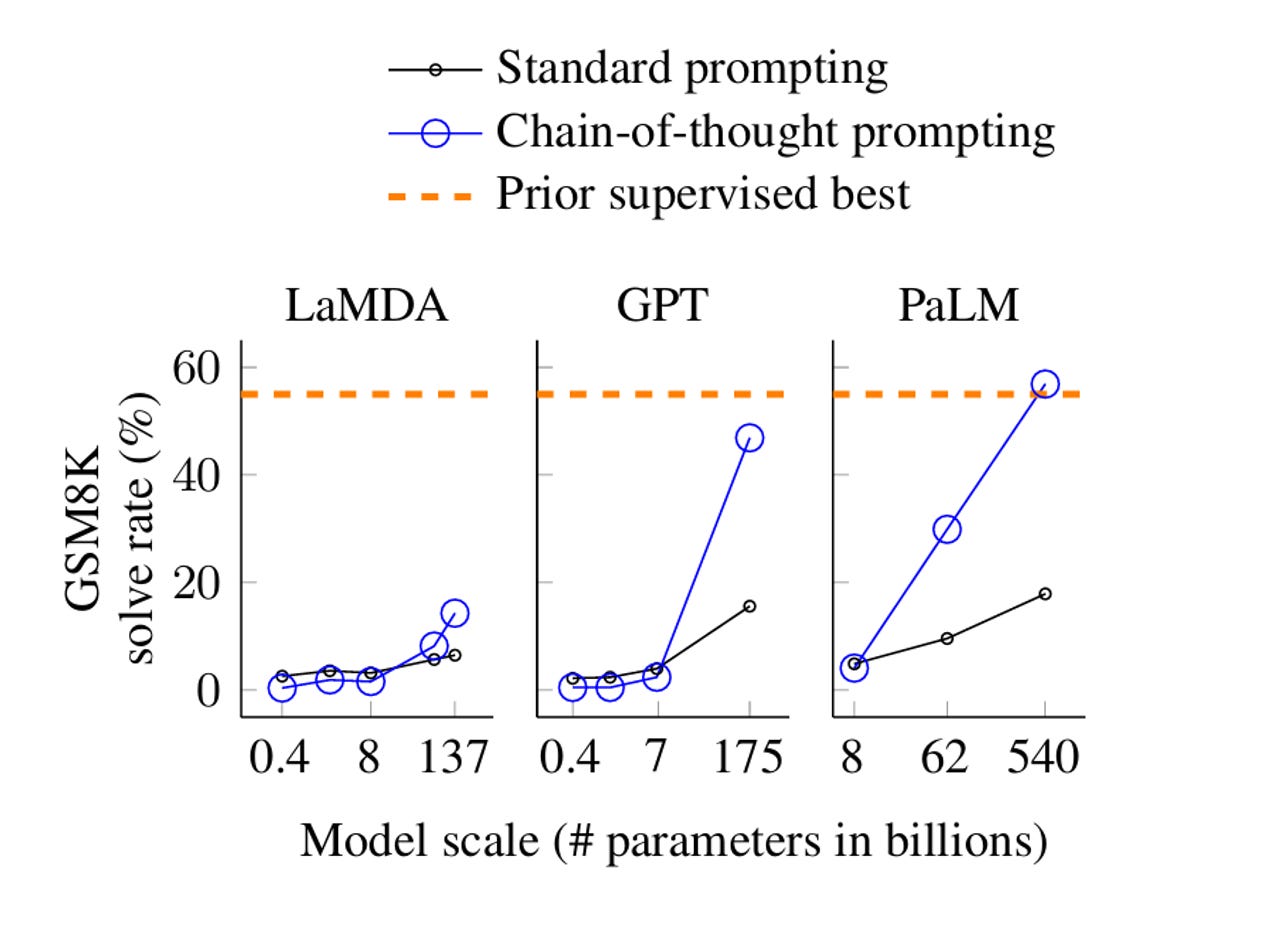

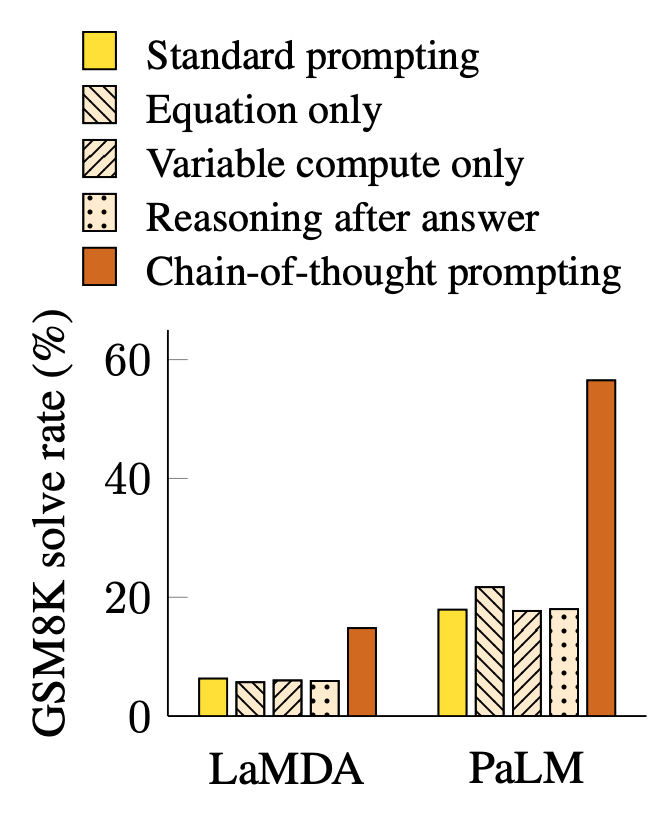

This technique boosted performance across a wider set of tasks ranging from language reasoning, to arithmetic, to symbolic logic—all without fine-tuning the base model. Curiously, CoT prompting elicited an effect only beyond certain model parameter sizes. This was the exact same result from the previous scratchpad work, as shown below.

Conceptually, that few-shot CoT prompting causes performance breakouts is similar to the fact that only students above a certain base intelligence threshold (i.e., middle-schoolers versus kindergarteners) can work through a reasoning scaffold after only a few examples.

The group’s ‘CoT after answer’ ablation hints at something profound. CoT prompting elicits performance gains only when the reasoning chain precedes the final answer, not the other way around. This suggests the model cannot produce the answer and then do post-hoc justification—similar to confirmation bias. Therefore, the model’s reasoning traces aren’t merely decorative, they actually do something to improve outcomes.

CoT prompting initially showcased the impressive ability for LLMs to mimic logical reasoning. But it also exposed a core limitation for these models: LLMs perform relatively well on problems that require single reasoning steps, yet frequently break down when introduced to more complex problems that require longer, multi-step solutions—something humans are particularly adept at.

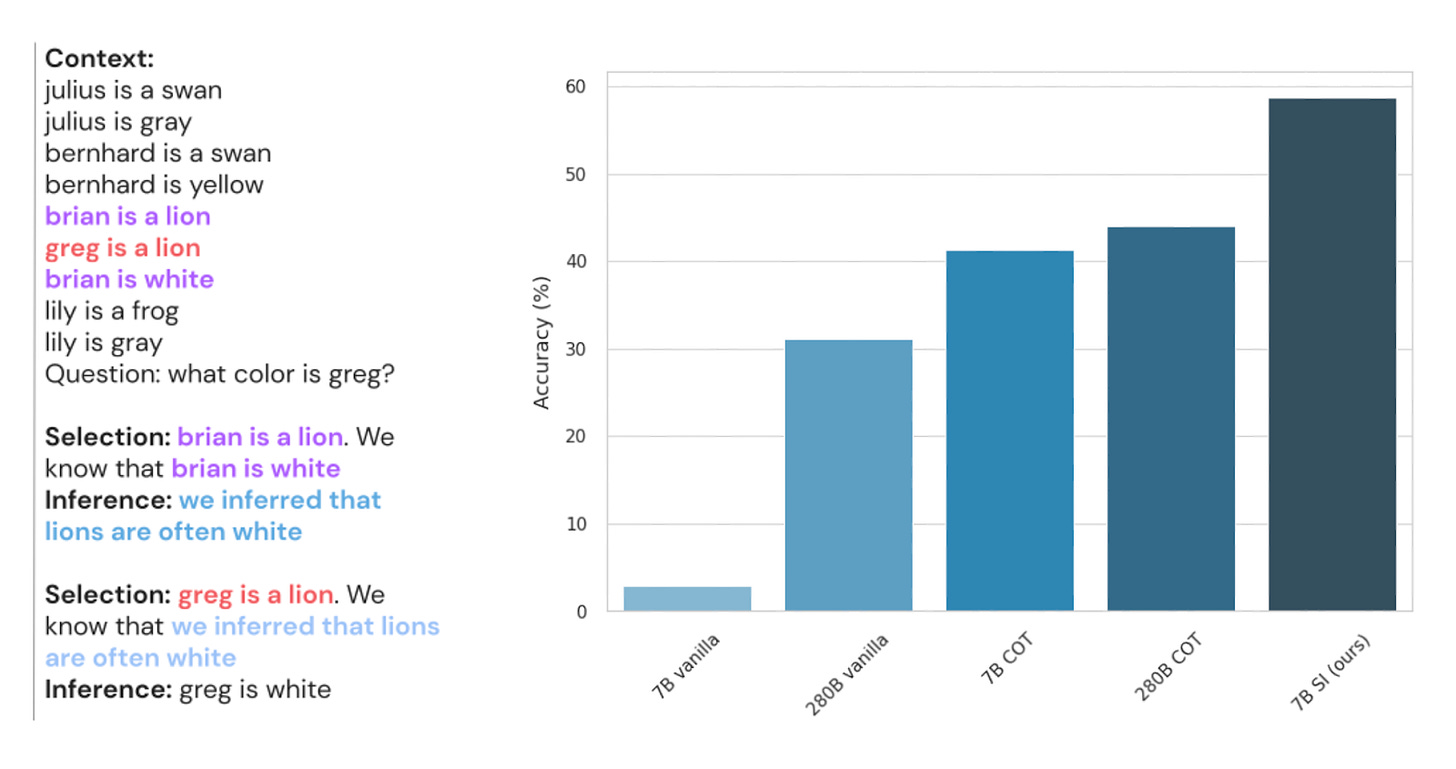

With this in mind, Creswell et al. at DeepMind introduced the Selection Inference (SI) framework to help models break down complex reasoning traces into a set of interpretable steps. SI works by iterating between two available steps for the model to choose from:

Selection: Choose a subset of relevant facts from the provided context (i.e., working memory) that are sufficient for one step of logical reasoning (e.g., “Brian is lion”, “Brian is white”).

Inference: Use only those selected facts to generate one new fact/intermediate conclusion (e.g., “Lions are often white”). This new fact is then added back to the context and the process repeats for several steps until the original question is answered.

Creswell et al. showed that SI increases average accuracy across 11 unique datasets when compared to both traditional and CoT prompting methods. Importantly, SI reasoning traces are uniquely causal. Each step follows from—and depends on—the previous step, ensuring a high level of human interpretability not previously seen with other reasoning methods.

If models compound logic towards a better solution, does that meet the definition of human reasoning? If a system can reliably produce seemingly-causal logical chains that generate correct solutions to complex problems, does it really matter if we call this genuine reasoning or sophisticated mimicry?

Bootstrapping Reasoning

“CoT proved that simple post-training techniques could amplify latent reasoning capabilities of sufficiently large base models. STaR exploits these capabilities…”

CoT spawned a wave of innovation as researchers raced to overcome obstacles preventing the technique from being used at scale, where questions about the genuineness of digital reasoning could be more fully answered. Two such obstacles were that human experts needed to either (a) construct enormous reasoning-libraries for SFT (expensive) or (b) provide in-context rationales alongside every query (tedious).

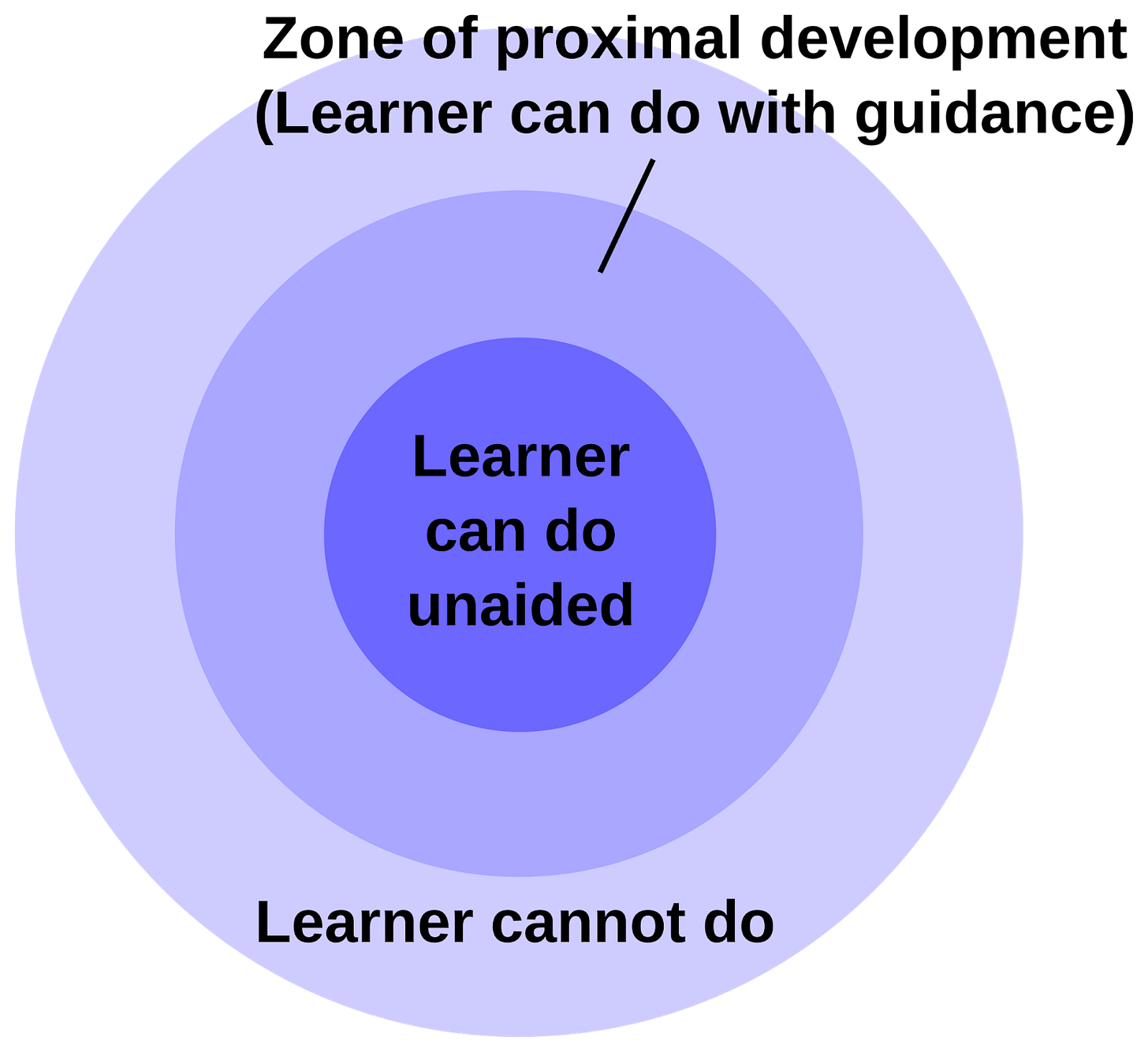

The solutions came from an educational psychology concept called the zone of proximal development (ZPD). The ZPD contains challenges that a student can overcome, but only with the support of a teacher, as illustrated below. They are neither too easy, nor too difficult such that the teacher’s explanation does nothing to help the student learn. Contemporary psychologist Robert Bjork describes these challenges as “desirable difficulties” because they maximize the effectiveness of learning.

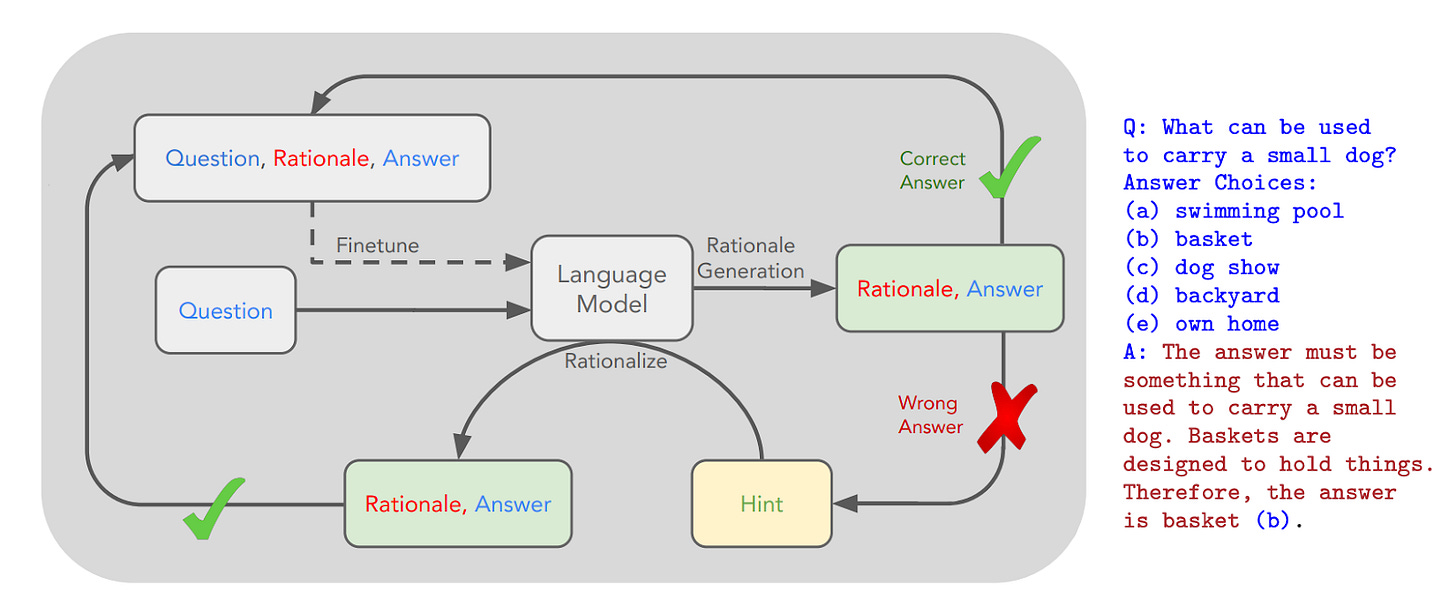

The self-taught reasoner (STaR) framework emerged in 2022, closely mirroring a pedagogical concept called scaffolding that directly builds upon the ZPD. Scaffolding requires a more competent peer—sometimes called the more knowledgeable other (MKO)—to provide initial help and then gradually taper off as the student learns.

CoT proved that simple post-training techniques could amplify latent reasoning capabilities of sufficiently large base models. STaR exploits these capabilities, using the LLM to build its own SFT library of correctly reasoned responses. Incorrectly reasoned responses are sent to an MKO—a human oracle—that corrects the output, allowing the model to then infill a plausible reasoning trace, as diagrammed below.

STaR sounds like a perpetual motion machine—a model teaching itself to reason better by training on its own outputs. But just as energy cannot be created ex nihilo, neither can reasoning capability. For STaR to work, information must flow in from somewhere—the oracle’s corrected answer or the latent reasoning capacity already compressed in the pretrained model weights. There can be no free (information-theoretic) lunch.

The authors noted that in order for the first STaR iteration to succeed, the base model must have a few-shot CoT success rate better than random chance. Intuitively, this means the latent reasoning signal of smaller base models (e.g., GPT-2) is insufficient to begin compounding. The authors used GPT-J as their base—a 6B parameter model about 4x larger than GPT-2’s largest model.

As an aside—this is now the third instance we’ve noted of scale dependence for contemporary post-training techniques. Once is a fluke. Twice is a coincidence. But three times is a pattern.

A Not So Random Walk

“Reasoning is more like a tapestry—a high-dimensional manifold composed of intermediate states (i.e., thoughts) connected by transformations.”

Unfortunately, reasoning is not a chain. Humans do not simply think harder or longer along a pre-ordained track that arrives at a conclusion. Reasoning is not a brute force activity, but instead an art of cleverness and creativity.

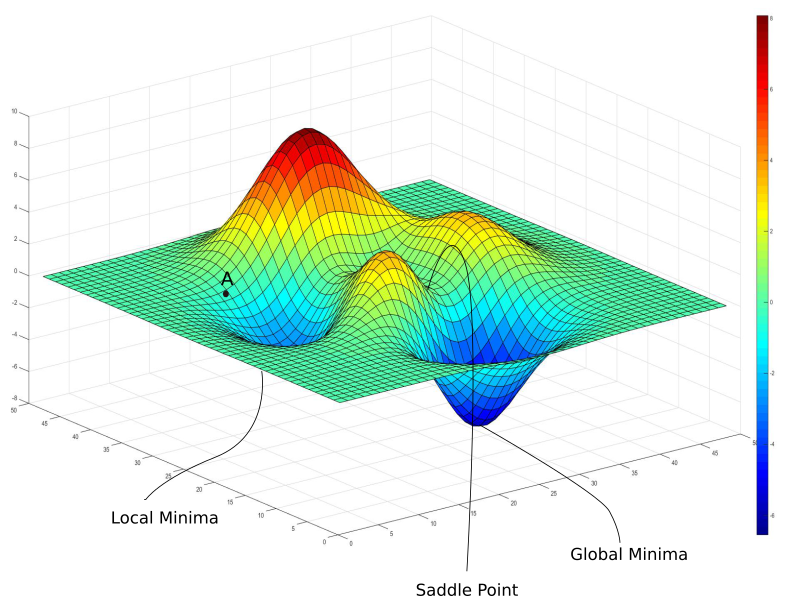

Reasoning is more like a tapestry—a high-dimensional manifold composed of intermediate states (i.e., thoughts) connected by transformations. Traversing this search space involves an initial, exploratory fanning out, efficient pruning of perceived dead ends, and a deliberate navigation towards some optimal point—whether the peak of a mountain or the doldrums of a valley.

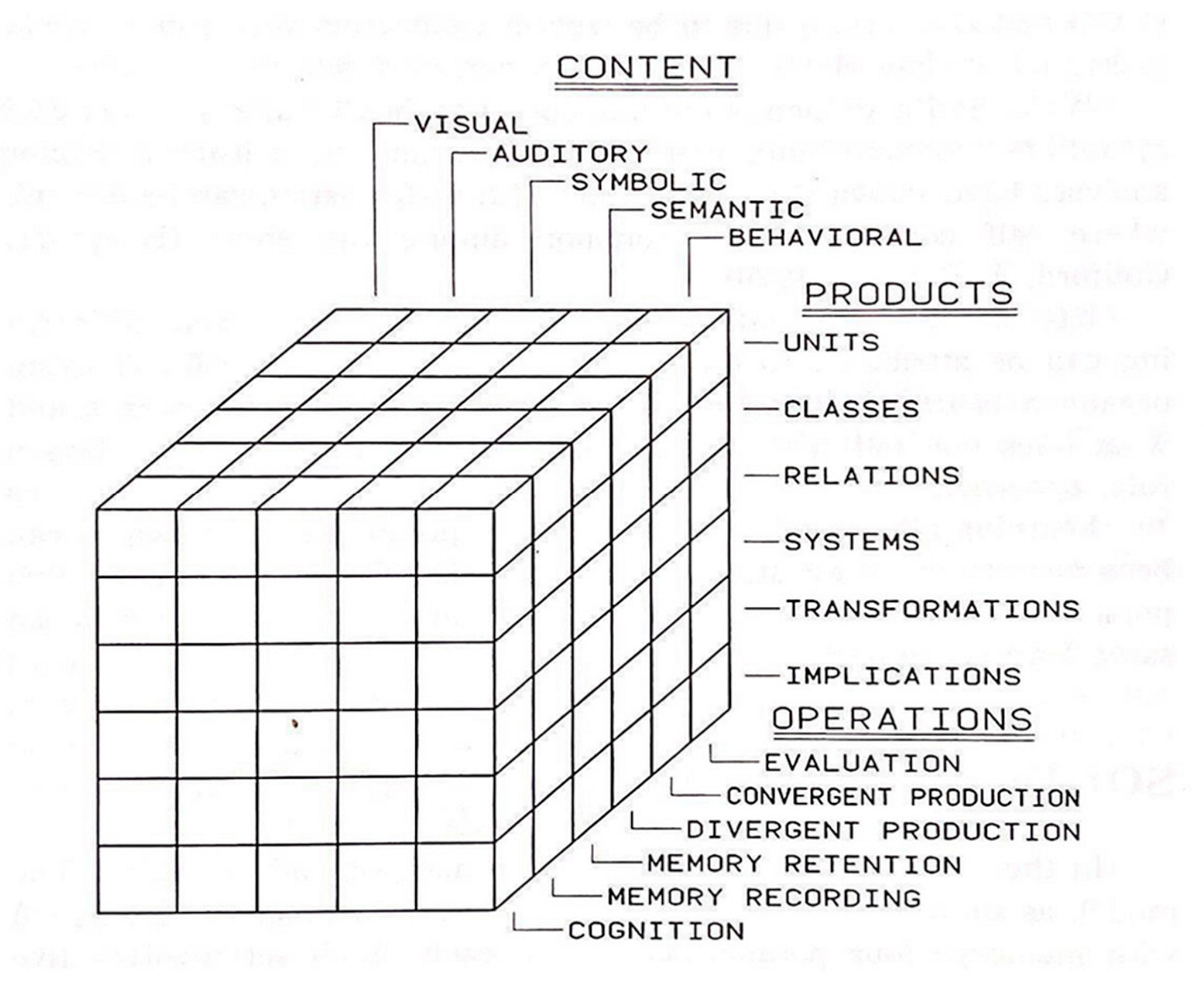

In his 1955 text on The Nature of Human Intelligence, psychologist J.P. Guilford introduced the Structure of Intellect theory. Guilford decomposed the entirety of the human cognitive apparatus into a grandiose Rubik’s Cube-like structure—each dimension representing a facet of human intelligence, as shown below.

Guilford became notorious for two opposing components in this system—divergent and convergent production. Simply, divergent thinking involves generating many unique ideas while convergent thinking systematically winnows these ideas into the single best, logical solution. ML reasoning traces fit neatly into Guilford’s model, inspiring a new wave of methods to advance reasoning capacity.

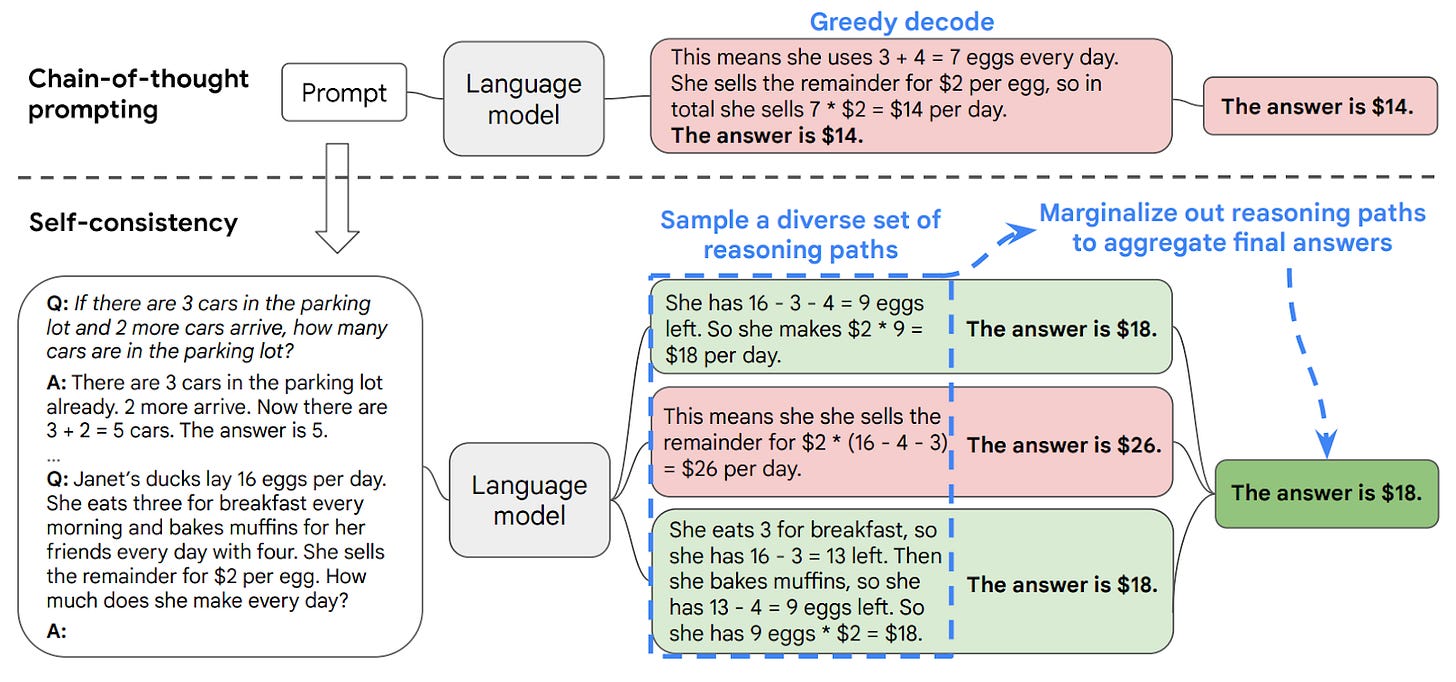

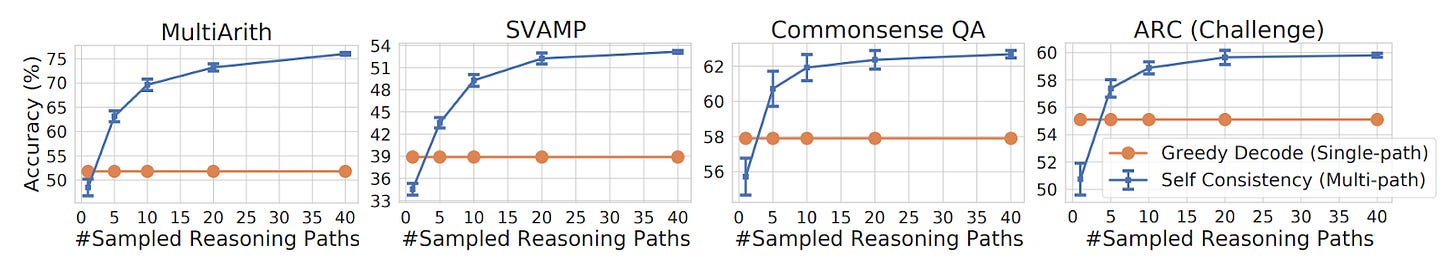

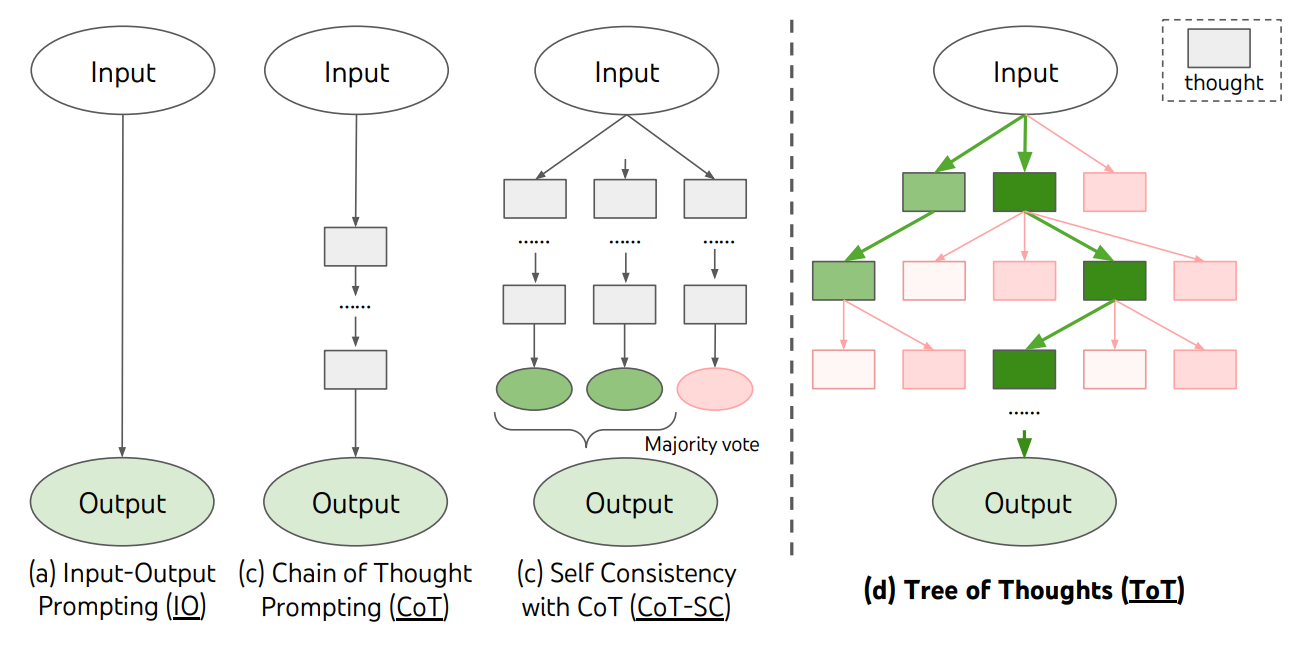

The Google Brain team improved upon the original CoT work in 2022 with the notion of self-consistency (SC). Specifically, they modify the LLM’s decoder—the part of the model that generates output tokens—to create multiple, divergent reasoning paths instead of simple next-token (i.e., greedy) decoding.

Greedy decoding generates reasoning traces where the nth token has the highest probability, which can make models fall into repetitive, formulaic phrasing that is brittle and imposes a ceiling on reasoning performance, as mentioned in the original CoT manuscript.

Meanwhile, SC involves sampling the LLM decoder to produce a set of reasoning paths then finding the most consistent answer to converge onto. This is predicated on the notion that reasoning errors are random and that it’s statistically unlikely for a wrong idea to be consistently repeated given enough samples (k).

The researchers plotted how SC improves accuracy over traditional CoT prompting, and unsurprisingly, they discovered that larger models have a greater benefit because smaller models tend to have noisier reasoning traces—challenging smooth SC averaging.

Self-consistency is a methodological bridge between Guilford’s divergent and convergent production modes. It forces an LLM to generate varied reasoning paths (divergent) before a majority-voting (convergent) mechanism.

It’s Time to Branch Out

“While standard CoT prompting blindly shoots a hopefully lucky trajectory across the solution manifold in one go, ToT treats reasoning as a deliberate, methodological search process.”

1955 was a monumental year for AI. Beyond Guilford’s work, Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, and Cliff Shaw wrote a computer program called the Logic Theorist (LT)—which many now view as the instantiation of machine reasoning.

This motley crew, which included a political scientist, an applied psychologist, and a computer scientist, initially created LT by hand using 3x5 index cards before scaling it to a mainframe computer that could prove dozens of mathematical theorems contained in Principia Mathematica.

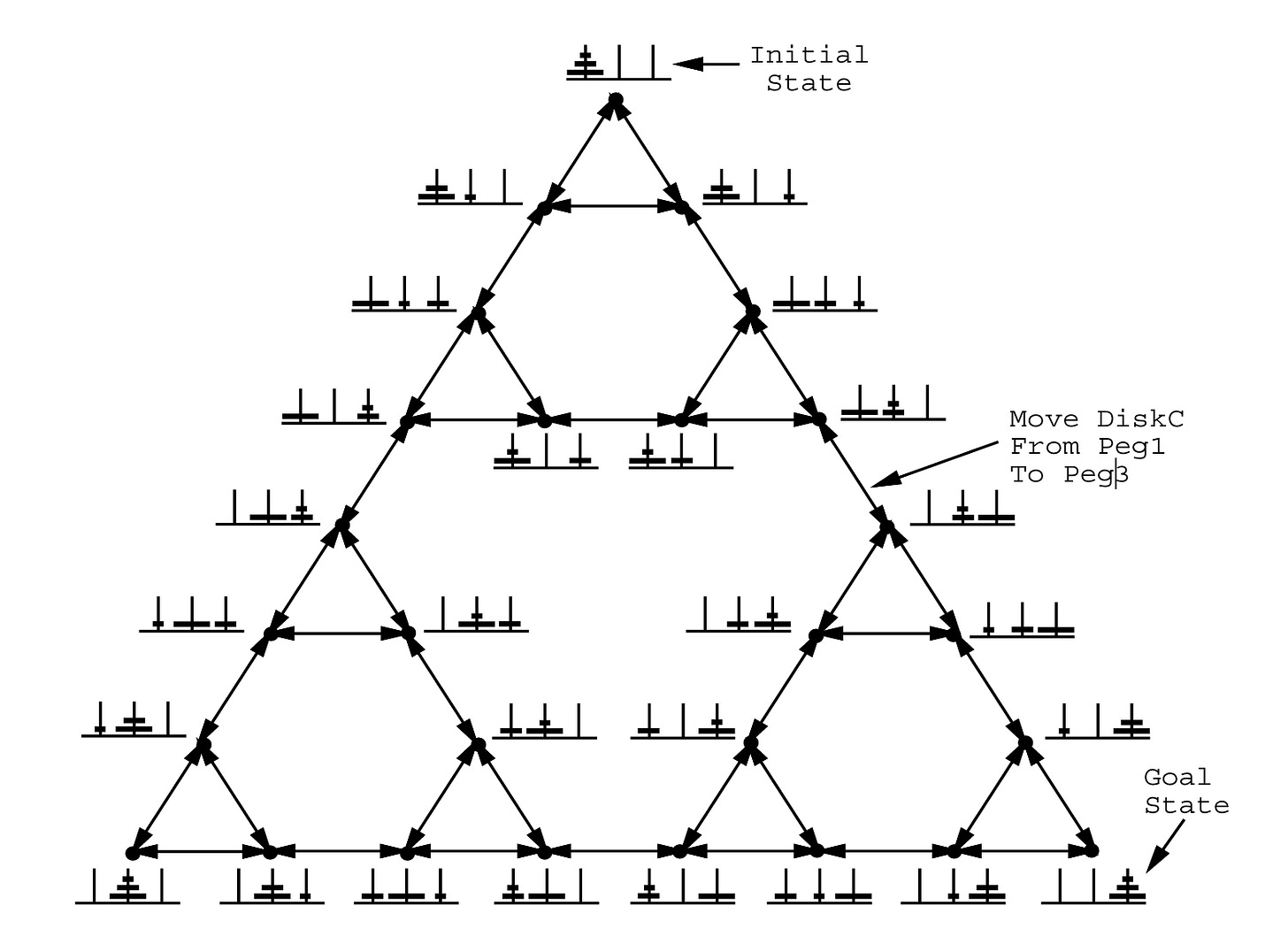

LT helped establish search trees as key reasoning structures within ML research. By performing elementary processes (i.e., transformations) on expressions (i.e., states), LT would create the branches of a search tree. They even installed pruning rules called heuristics that could halt reasoning chains unlikely to result in a solution.

In the early 1970s, Simon and Newell penned Problem Space Theory, which describes logical problem solving as a heuristic-guided search through a “problem space.” Building on their work with LT, problem spaces are made up of symbolic states and operators that transform one state into another.

Problems are defined as an initial state, a goal state, and a set of path constraints that affect problem-solving. This framework resembles a solution manifold, with reasoning offering a method to traverse this landscape toward successful outputs at local or global optima.

Simon and Newell describe an early reasoning concept called search control that provides the directional gradient toward these optima (i.e., solutions). In search control, the reasoner selects an operator, applies it to the current state to produce a new state, and decides whether to (a) accept the new state or retreat, (b) decide a solution has been reached, or (c) quit.

Gradient math only works on smooth, differentiable surfaces, but these problem spaces are made up of discrete states. Nonetheless, they’re conceptually similar insofar as they both allow local information to guide global search problems—a core idea that still underpins today’s reasoning models.

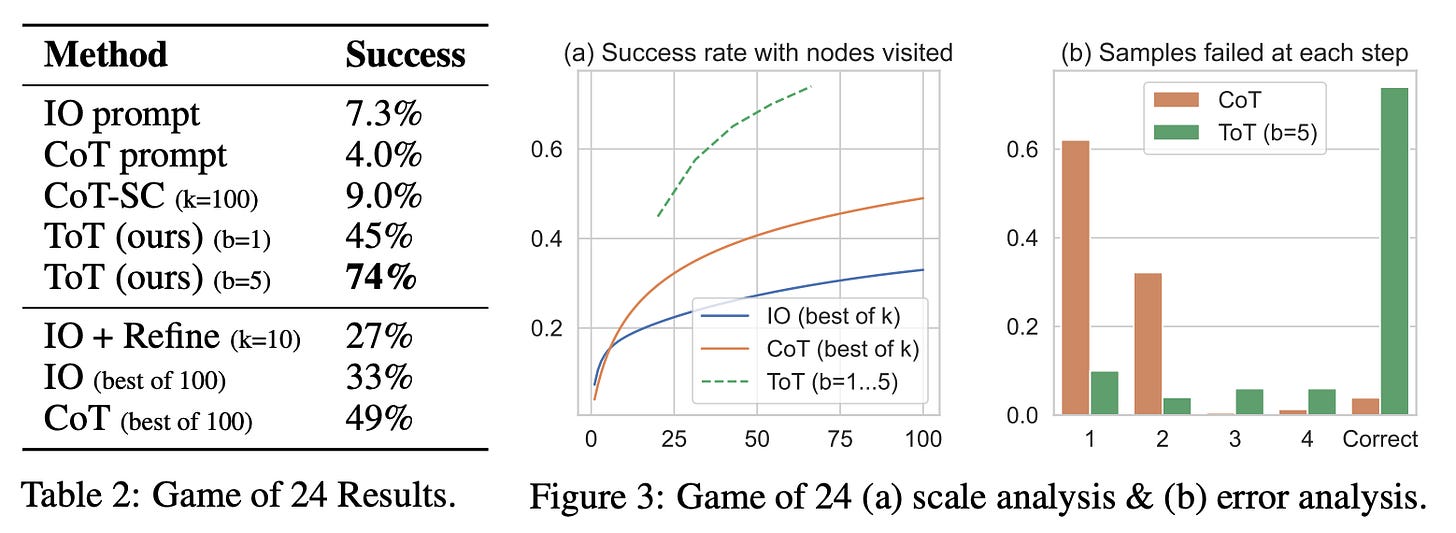

Researchers from Google and Princeton leveraged problem space theory when they developed the tree-of-thought (ToT) reasoning framework. Recall that the previous SC method still relied on post hoc majority-voting of independent, autoregressive reasoning paths. By contrast, ToT uses a branched reasoning structure, as diagrammed below.

The biggest change from SC is that trees of thought have interdependent reasoning paths. These paths (branches) can share common parent nodes. Unlike the hand-drawn heuristics present in Logic Theorist, ToT turns the LLM inward—using the model as a judge to decide which next step to take. Though this is flexible, it inflates inference costs since the model must perform nested reasoning about its own thought process.

The ToT framework is a mechanical instantiation of Simon and Newell’s search control. While standard CoT prompting blindly shoots a hopefully lucky trajectory across the solution manifold in one go, ToT treats reasoning as a deliberate, methodological search process. It decomposes its traversal into discrete thought steps—intermediate coordinates on the surface. It uses the LLM itself to evaluate its current state, deciding whether and how to proceed to the next state.

Taking it Step by Step

“Reinforcement learning has emerged as a key method to teach modern LLMs how to effectively reason, using digital rewards to direct the model toward more desirable outputs. Thus, your reasoning model is only as good as your reward model.”

The introduction of ToT methods significantly improved the reasoning capabilities of LLMs through branched logic. But this increased performance comes at a price. With reasoning traces growing in complexity, hallucinations within the chain-of-thought and the subsequent logical missteps become increasingly necessary to mitigate. One approach to tackle this issue is through optimizations to the RL process directly.

RL has emerged as a key method to teach modern LLMs how to effectively reason, using digital rewards to direct the model toward more desirable outputs. Thus, your reasoning model is only as good as your reward model. The reward model can be thought of as an external judge that evaluates the LLM’s output and selects how the model should update its weights to improve for the next question.

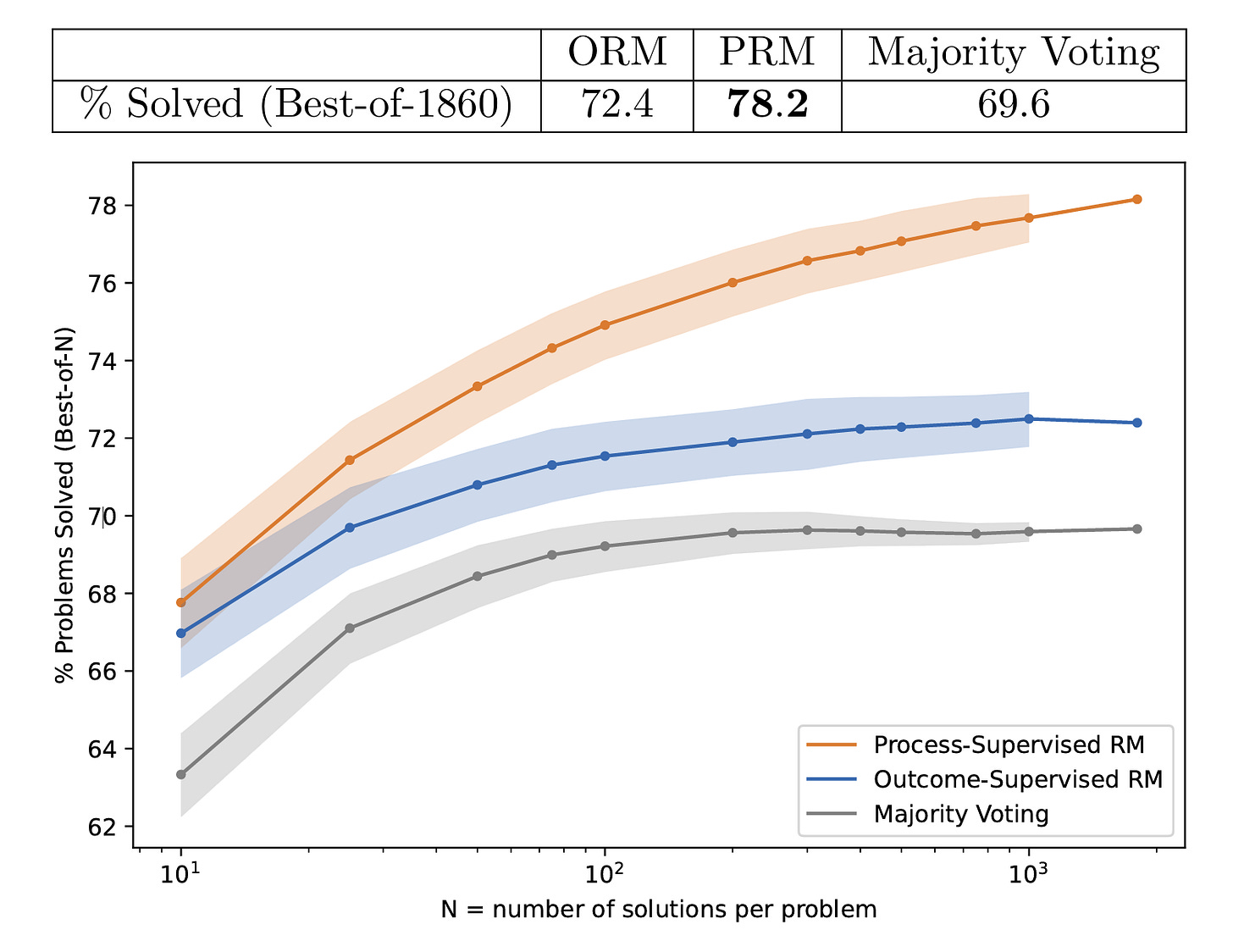

In the 2023 paper Let’s Verify Step by Step, Lightman et al. at OpenAI explored how to train reward models for optimal reasoning performance on the MATH dataset. They explored two main approaches: outcome supervision and process supervision.

The key difference between the two lies in what information the reward model receives to guide how the base LLM should update its weights. Outcome-supervised reward models (ORMs) are trained using only the final result of the model’s chain-of-thought, while process-supervised reward models (PRMs) receive feedback for each step along the reasoning path.

Creating an ORM is easy as the MATH dataset has automatically verifiable answers. To train the PRM, Lightman et al. had to rely on human labelers to score intermediate reasoning steps on model-generated solutions.

In the bake-off, they used GPT4 to generate several candidate solutions per MATH problem and asked each reward model to score them and select the solution with the highest rank. They then plotted the percentage of MATH problems where the reward model’s selected highest-ranked solution is the correct final answer. The PRM outperforms the ORM and simple majority voting across the board.

PRMs are likely more performant because they can pick up on where reasoning goes wrong, not just whether the final answer looks correct or not. This is a particularly important point for our original motivation because many hallucinations can result from intermediate process errors such as incorrect mid-chain claims, algebraic errors, or logical jumps. PRMs reduce these logical missteps as they explicitly reward the step-by-step accuracy and logical continuity required for solving more complex problems.

We’ll Do It at Test Time!

“Test time scaling is essentially an energy tax paid for inefficient or incomplete internalization of reasoning during training.”

We’ve chronicled how decades-old insights into human cognition have compounded to yield something akin to artificial reasoning. Broadly, these innovations comprise reasoning structures—frameworks and pre-charted pathways that LLMs leverage as scaffolding while negotiating reasoning tasks. We’ve yet to address the physiological burden of reasoning.

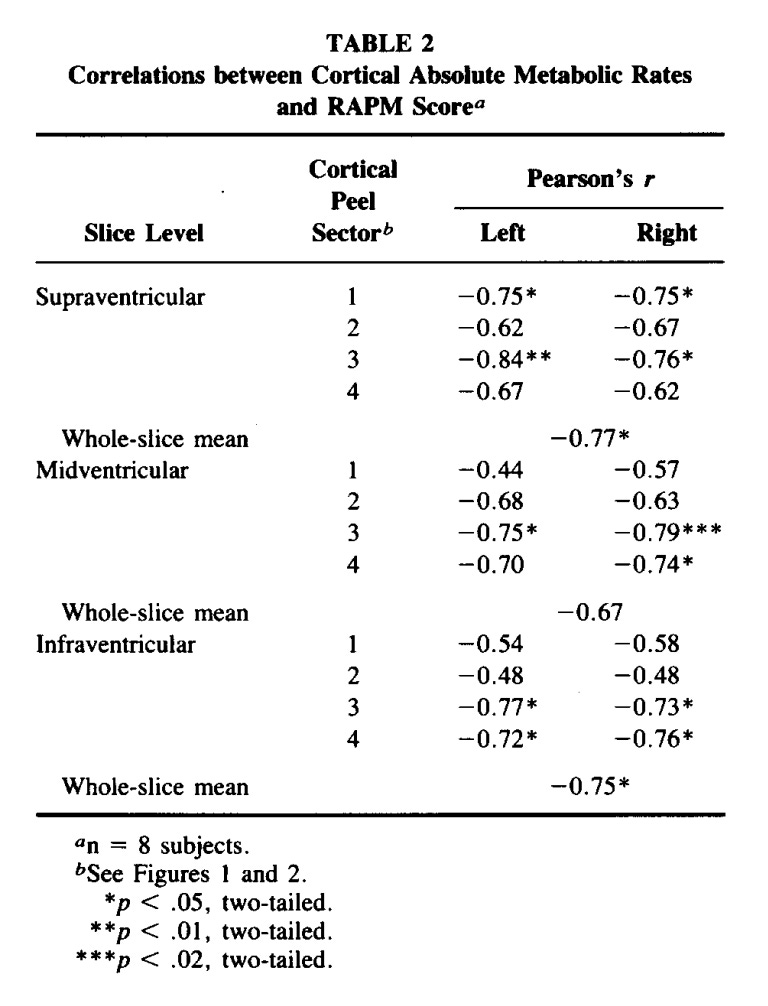

Why does deep thinking feel exhausting? Because it is. In the late 1980s, a research group measured dozens of individuals using positron emission tomography (PET) scans while they undertook an abstract reasoning task. By using a glucose analog tracer dye, the researchers could quantify glucose metabolic rates across human brain sections.

Interestingly, they discovered that humans performing worse on reasoning tasks—folks who were struggling through the tasks—utilized more glucose than their peers who breezed through problems. As shown below, all statistically-significant associations between task score and absolute glucose metabolic rate were negative. Therefore, task difficulty creates increased metabolic demand.

Test-time scaling (TTS)—a hotly discussed concept at the razor’s edge of ML research—has a deep, conceptual overlap with neural glucose metabolism. TTS refers to methods that boost the amount of computation (i.e., tokens) expended during LLM inference, without altering the base model’s underlying weights or representations.

Structural reasoning methods improve the efficiency of inference by shaping solution trajectories through a model’s latent space, but they are imperfect. Meanwhile, TTS improves performance by increasing the probability of generating a productive trajectory.

TTS is essentially an energy tax paid for inefficient or incomplete internalization of reasoning during training. This is the same conclusion from the PET imaging study. Worse performers utilized significantly more glucose while reasoning—the same way that suboptimal reasoning models compensate by upping their test-time token metabolism.

How far can TTS take us from here? This is a question the entire field is grappling with. Consider the Infinite Monkey Theorem—a monkey tapping random keys on a typewriter for an infinite amount of time will almost surely type out the entire works of Shakespeare. Similarly, if provided infinite tokens, can LLMs reason their way to solutions for any problem?

This thought experiment pokes at the boundary between theoretical infinity and physical reality. We do not have infinite tokens. But how far can TTS take us in a world where the price of an inference token has plummeted by 1,000x in recent years with no end in sight?

It’s reasonable to think that even a precocious kindergartener couldn’t conquer a college-level vector calculus exam. Having years in isolation to think, to expend glucose, wouldn’t make a difference. Isaac Newton, meanwhile, famously developed fluxions—a type of derivative calculus—to express his ideas about planetary motion.

Are we in a regime where pre- and post-training techniques have taken us far enough—one where we are content to pay an inference-time token tax if TTS can drive us towards AGI? Are our base models today more like the kindergartener or Newton? If the former, when will we arrive at the latter?

TTS in Practice: o1 and R1

“Crafting a more potent reasoning scaffold and driving more tokens through it at inference time confers dramatic performance gains across diverse, multi-step problems.”

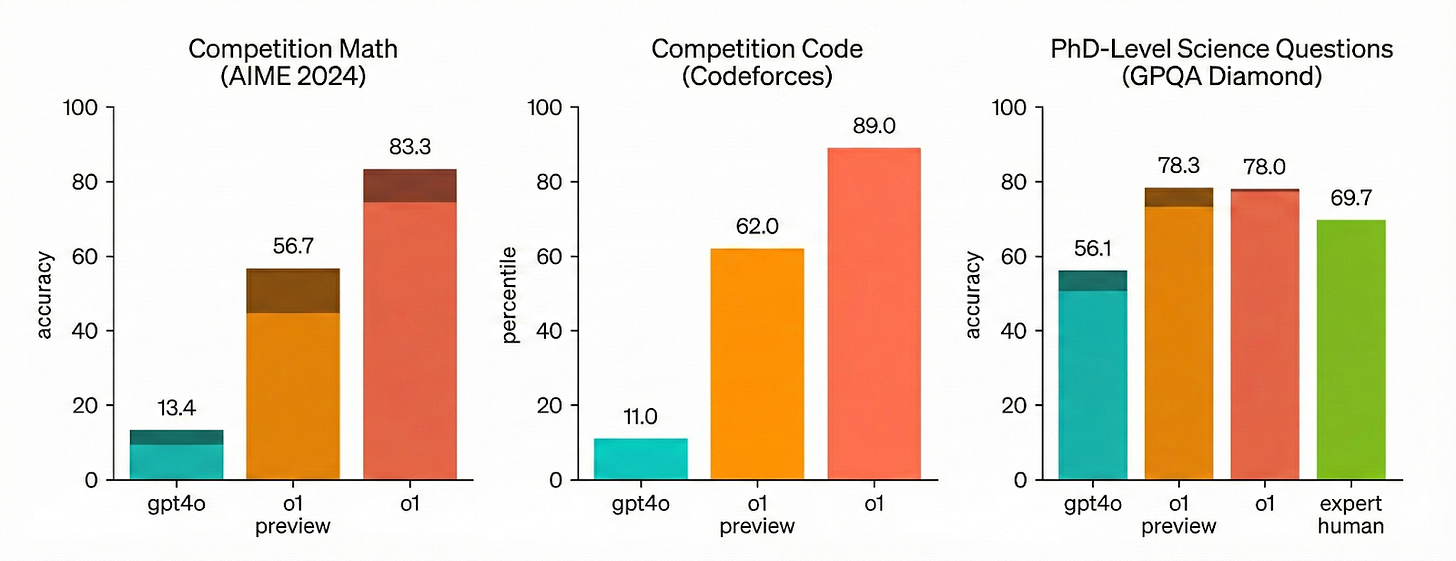

The o1 model series from OpenAI catalyzed the TTS dialogue in earnest, which they describe in their blog—Learning to Reason with LLMs. For starters, OpenAI employed a large-scale RL campaign to amplify the base model’s fundamental reasoning capabilities.

Purely through RL, OpenAI showed that the model’s pass@1 accuracy scaled from ~30% to ~70%. This metric describes the LLM’s ability to generate a correct response on its first attempt—an important capability when applying TTS because errant, interim logical steps can explode inference costs.

After having structured the base model’s reasoning capabilities, OpenAI measured how expending more compute at inference time yielded additional performance gains across a variety of tasks, as plotted below.

Given the limited public information from OpenAI, it’s difficult to dissect o1’s construction and how it may map back to a cognitive or biological prior. It’s clear, however, that crafting a more potent reasoning scaffold and driving more tokens through it at inference time confers dramatic performance gains across diverse, multi-step problems.

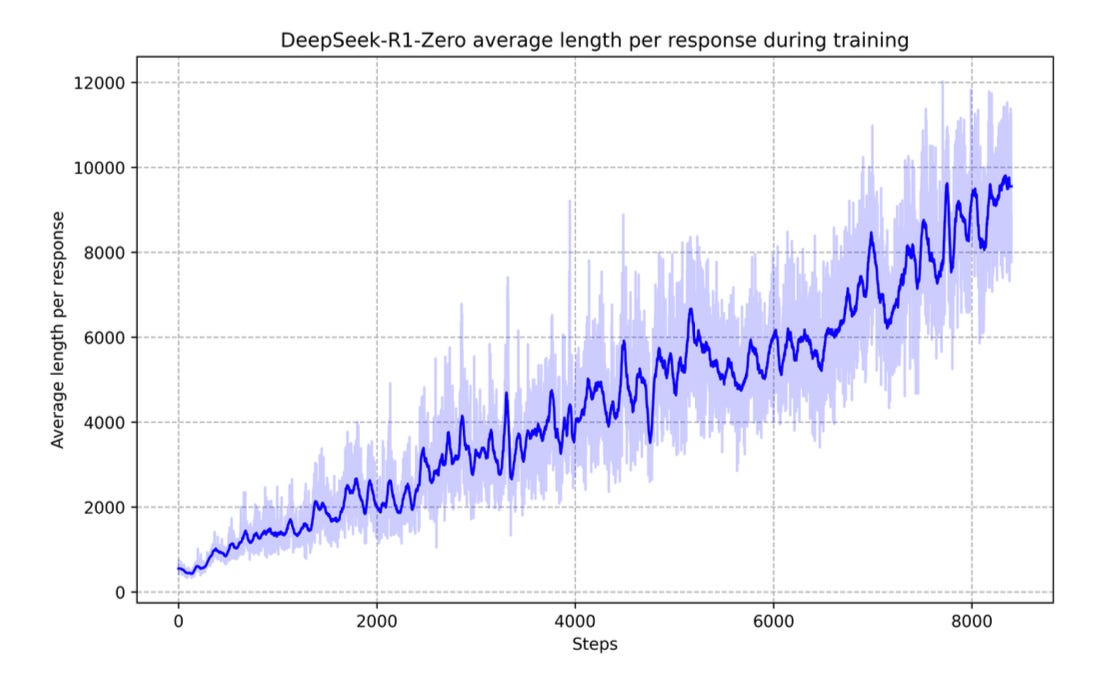

DeepSeek—the AI-focused subsidiary of Chinese hedge fund High-Flyer—created shockwaves this summer by releasing an open-source model series called R1. DeepSeek released a detailed manuscript alongside its models, providing key insights into how RL, supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and TTS can combine to create exemplary reasoning capabilities.

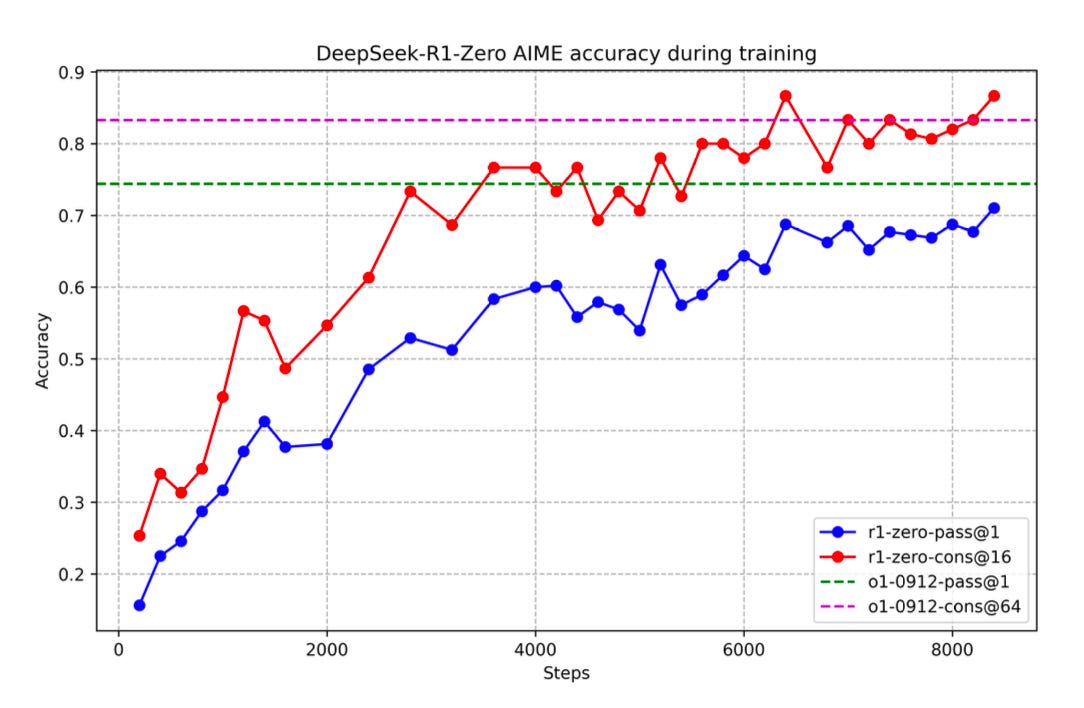

The group first set out to replicate o1’s reasoning performance with a pure RL approach. Using their own base model, DeepSeek-V3-Base, they built a deliberately simple RL algorithm that instructed the model to think first then produce an answer. By rewarding correct answers, this digital natural selection process enhanced V3-Base’s average output length and correctness across tasks—leading to their first reasoning model called R1-Zero. However, R1-Zero suffered from poor readability, prompting DeepSeek to try a second, more robust approach.

Motivated by R1-Zero’s usability shortcomings, DeepSeek concocted an involved post-training process involving an initial salvo of cold-start data—a thousand-sample tranche of curated, reasoning samples. Following a brief round of SFT, the group performed a similar round of reasoning-centric RL. They then put the model through another round of SFT, this time to broaden the LLM’s capabilities across interdisciplinary domains before a final round of RL—producing DeepSeek R1.

At inference time, R1 uses temperature sampling as its TTS mechanism, producing multiple reasoning traces that undergo majority voting. The consensus output is presented to the user, demonstrating performance completely on par with the o1 series.

Importantly, DeepSeek also distilled R1 into smaller models such as <10B parameter versions of Llama and Qwen. While there was some performance degradation, the implication is that reasoning signals extracted from large teacher models can be transferred to smaller, more scalable models. Perhaps using TTS on a smaller, distilled model format could deliver frontier-like LLM capabilities with much smaller economic footprints.

Parting Thoughts

“We have learned that this stepwise transferral from human to machine is valuable. The latest research into test-time scaling is forming a new scaling regime for frontier models.”

We live in an extraordinary time. Decades of metareflection on our own cognitive abilities and the biological structures enabling them have produced a bounty of mechanisms underpinning reasoning. Many precocious individuals—from economists to psychologists to computer scientists—have spent their careers closing the latency gap through which these mechanisms become installed in silicon.

We have learned that this stepwise transferral from human to machine is valuable. Each atomic unit of human reasoning compounds, manifesting into a cerebral structure that has begun approximating higher-order cognitive capacity. The latest research into test-time scaling, which is analogous to mental exertion, is forming a new scaling regime for frontier models.

Channeled through even more modern structures, TTS is likely to create a new dawn in machine learning research—one where we begin to peer inside these labyrinthine, hidden model layers to learn the rules of this new game. How far can TTS take us? What are the practical limits of implementation? If we peer far enough ahead, can we see where TTS ends and what to do next?

In our next essays, we’ll grapple with some of these questions—including a discussion of arguments made during both reasoning-focused workshops at NeurIPS 2025, which are now just two weeks old.

It's interesting how you highlit the space between stimulus and output as the core difference; could you elaborate on how inductive human bias mite bridge that gap in TTS?